Langkawi: An Island Refuge

Rain is beating an insistent tattoo on the hotel roof, and as I observe the drops pounding the foliage outside our room, I am acutely aware that my view is a melange of different shades of green — yet devoid of the manicured terraces and gardens that are the hallmark of most tropical resorts. Indeed, as I have already discovered, the Langkawi experience contrasts markedly with that of most of 21st-century Southeast Asia.

Only days before, we had been in a much drier Singapore, with its skyscrapers, harbour promenades, shopping centres galore, a teeming mass of humanity and a veritable ‘jungle’ of metal barriers to accommodate the upcoming Formula One Grand Prix through downtown streets. Still, our local tour guide proudly assured us that 15 per cent of the city-state’s land area is retained as jungle, “containing more biodiversity than all the forests of the North American continent combined.” However, our visit to Singapore’s fascinating zoo also revealed that fewer than 300 lions still roam free in the ever-dwindling forests of neighbouring Malaysia, while the seemingly insatiable demand for ivory and habitat loss continue to take an accelerating toll on Asia’s elephant herds and rhinos. The heavy stain of smoke hanging across Singapore’s skyline from forest fires across nearby Sumatra served to aptly reinforce the depletion of the region’s natural heritage.

Even the recently-opened Gardens by the Bay seemed rather symbolic of the way in which nature here has been tamed and reconfigured for a family-friendly audience. The ‘super trees’ that provide the visual centrepiece for the gardens comprise a spectacular confection of flower-like structures — complete with skywalk and daily light show — that arch out over real trees and manicured beds below, while the equally spectacular waterfall within the ‘Cloud Forest’ also clearly resonates with locals and tourists alike. Yet, the very contrivance of these features and their idealisation of nature seems somehow more evocative of what Southeast Asia has lost — and continues to lose — rather than of true progress. The juxtaposition of the super trees against the Star Wars-like profile of the Marina Sands hotel — signposting Singapore’s casino — is just a little too symptomatic of a world that has turned its back on nature, at least in its raw, un-sanitised form.

The contrast with our new-found ‘home’ on Langkawi Island — just over an hour’s flight north of Singapore — could hardly be more striking. The Langkawi Global Geoforest Park was attributed World Heritage status in 2007. It embraces some of the oldest and most spectacular topographic formations within Malaysia, while the carpet of very real jungle spread around and across them is framed by spectacular coastlines and luxuriant mangrove forests. Outlying islands also form part of the ‘geopark’, while Thailand’s Ko Sarai — visible to the north, but just outside the geopark — is also layered by sharply defined peaks and a broad expanse of remnant rainforest.

Indeed, this area has remained relatively remote and little-known throughout most of the 20th century. Until occupied by the Japanese in early 1942, it was perhaps best-known for the British Army’s penal facility on the neighbouring Andaman Islands. Today, the northern coastline of Langkawi Island still retains a cove colloquially known as Skull Bay, where locals despatched escapees from both the army detention centre and a Thai prison on Ko Sarai before they had the opportunity to foment any ‘trouble’ with local women.

Fortunately, in 2015 the term Andaman is more commonly associated with rather more salubrious accommodation and a somewhat more welcoming arrival experience. Sitting on the edge of Datai Bay, near the north-western tip of Langkawi Island, The Andaman resort offers guests a rare sense of engagement with landforms and ecosystems that date back some 550 million years. Indeed, most of its visitor facilities are located inside the jungle’s margins, with a swathe of mature trees and undergrowth separating the greater bulk of the hotel from an expansive, sand-lined beachfront. The hotel’s swimming pool wends its way between islands of trees and underplanting, while the entire forest frontage provides an attractive playground, roost and food source for a variety of local wildlife.

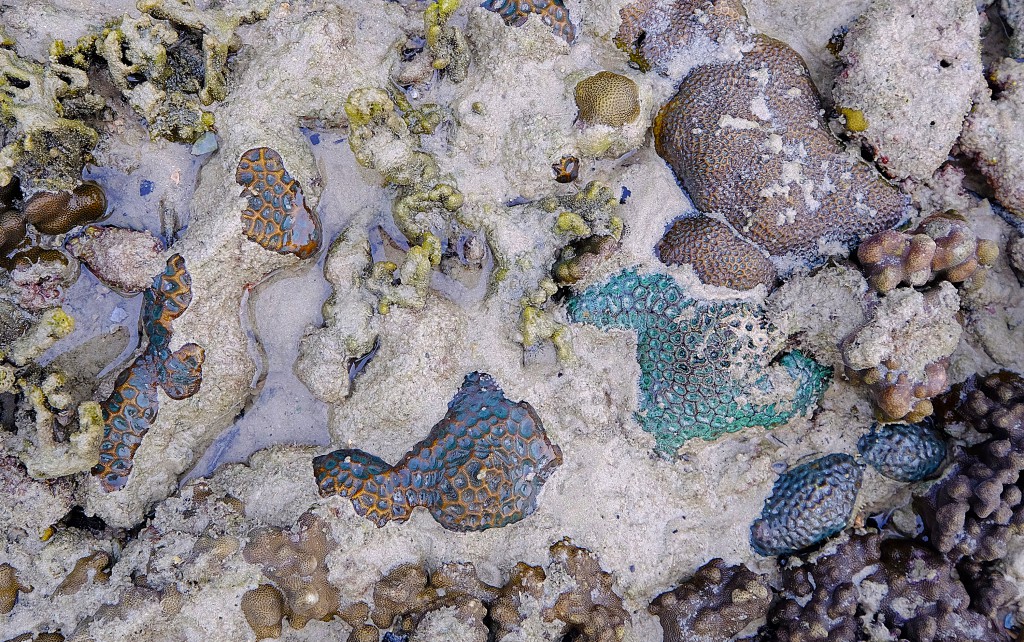

However, in December 2004, this swathe of vegetation contributed to far more than just the hotel’s aesthetic appeal, as it broke up a series of 5-metre waves — part of the Boxing Day Tsunami — that swept across the Datai Bay beachfront and hotel grounds. Nearly 11 years on, the scars of that tragic event are still periodically unveiled. A low tide in the course of our stay reveals much of the local coral reef still caked in sediment, with just the bay’s brain coral and one rather forlorn-looking green coral managing to lift their ‘heads’ above this debris. The Andaman’s own constructed coral ‘garden’ — in a large pool, complete with reef fish — offers insight into just how much has been lost around the margins of the Andaman Sea and Bay of Bengal as a result of that one tragic event.

Thankfully, the effects on other local flora and fauna have been less enduring. Even those guests seemingly wedded to their poolside loungers and the beachfront find it impossible to ignore the troops of dusky monkeys and macaques gambolling in the tree tops, while a surprisingly large number of return guests seem only too happy to regale newcomers with tales of agile primates raiding their rooms in the hunt for chocolate bars and sugar. More commonly, though, the animal inhabitants simply swing through the tree canopy and chatter loudly, watched warily by hotel staff. On the other hand, my leisurely swim across the swimming pool turns to a brief moment of panic as I suddenly realise I am gaining on a monitor lizard, while a flock of hornbills perched noisily above our loungers one morning present a rather different form of ‘hazard’.

Other stories of close encounters abound — from the sudden meeting with a small ringed snake outside my front door to the paw prints that have us firmly convinced a leopard had been down to explore the beachfront overnight. Each evening, the walkways behind the accommodation wings turn into viewing platforms as flying lemurs slowly prepare to launch themselves — in highly aerobatic fashion — from tree to tree. The estuary next to the hotel is renowned for mud banks on which monitor lizards laze and soak up the rays, while overhead, brightly-coloured kingfishers — brown and orange, as well as blue and green — dive from cover and squirrels turn the trees and branches around us into an aerial super-highway. On the walk down to one local beach, we hear the squeal of the ‘night-time gardeners’ — a herd of wild pigs — but these soon disappear, to be replaced by the cries of ever-watchful macaques. Dolphins are clearly visible offshore one evening, while fishing eagles and ospreys hover over our waterfront walks.

Away from The Andaman, day trips to the ‘real’ jungle, mangrove forests and the Kilim Karst Geoforest cater for visitors seeking a deeper understanding of Langkawi’s remarkably diverse ecology. However, for those wanting more of an overview of the island, a gondola ride to the top of Mt Machinchang serves to both extol the panoramic virtues of Langkawi’s limestone spine and scare the living daylights out of anyone even remotely nervous of heights: the initial ride to the middle station is extreme enough, but the final, peak-to-peak approach to Mt Machinchang is even more breath-taking. The skywalk from near the gondola’s top station — traversing a chasm between two peaks — is no less challenging for the faint-hearted.

Unfortunately, the faux Asian market village at the foot of the gondola reeks of commercialism with a Disney touch, but little real substance. Rather more appealing is the quick side trip to the Seven Wells Waterfall close by. Although the steep climb to the pools above the waterfall in 30-degree Celsius temperatures and 90 per cent humidity takes a rapid toll on both calf muscles and fluid reserves, the view is well worth the effort and, of more immediate importance, the water is wonderfully cool.

Both the gondola ride and clamber around the falls also serve to remind us just how precious this ‘geopark’ experience is. Even with World Heritage status, there is a real sense that Langkawi’s parklands are under pressure. Housing, roading, plantations and tourist developments — from low-key lodges nestled in the jungle to golf courses carved out of it — are already eroding parts of the geopark, and even though jungle is spread across the northern spine of Langkawi, its key reserves are split in two, with the Machinchang Cambrian Geoforest Park and the larger Kilim Karst Geoforest Park at opposite ends of the island.

Looking out from The Andaman’s beachfront one afternoon, I watch as eight Thai fishing boats belch black diesel into the air and scour the waters between Datai Bay and Ko Sarai. Locals talk of fish stocks running out within 5 to 10 years, and of the fishermen then resorting to piracy to eke out some form of near-subsistence living. It’s not a vision for the future that sits well with the spectacular panorama in front of me, but I suppose desperation breeds extreme responses. Closer at hand, the sight of plastic bottles strewn along roadsides is a perennial issue, while the odd dead monkey and even a dead monitor lizard on local roads reflect the fundamental incompatibility of wildlife with many of the accoutrements of human ‘civilisation’.

Even so, it would be churlish to suggest that Langkawi is anything less than special. Throughout much of Southeast Asia, natural ecosystems, already reduced to shredded fragments among roads, settlements, marinas and palm oil plantations, simply cannot be replaced by symbolic re-creations. By contrast, Langkawi’s geopark offers a glimpse of the price to be paid for uncontrolled human expansion, a short-term refuge within which stock can be taken of those things that will be really important and valuable in the future.

Such engagement also has a frisson of danger: the paw prints in the sand and the inadvertent meeting with a tiny snake. Still, resorts like The Andaman, and the environment that supports them, make such interaction a truly positive experience. In the process, such contact educates, motivates and inspires: it is hard to imagine anyone leaving The Andaman and Datai Bay without newfound appreciation for the forests and coastal habitats that surround this resort enclave, or greater understanding of the wealth of wildlife that even a small area of forest supports. Ultimately, such experiences may well be all that stands between the retention of the last of these ‘wilderness’ areas and the blade of the bulldozer.