Art and Cuisine in Mexico City

Mexico City is a study in diversity and contrast. From the enduring enclaves of Chapultepec, Coyoacan and the Centro Historico to the hip neighbourhoods of Condesa, Roma and Polanco, nods to tradition activate a network of vibrant contemporary culture in the guesthouses, museums and restaurants of this complex metropolis.

I arrive at Mexico City’s Red Tree House during happy hour. The smell of fresh lilies permeates the space, and I relax on the sofa with a smooth cabernet while my bags are taken up to my room. I feel at home already.

Looking around the living room, a brightly coloured, intricately patterned coyote raises its head in a howl, a life-size figure — a cross between Mickey Mouse and a Buddha — sits cross-legged in the corner, large paintings adorn the walls, and a grand piano waits to be played. A patterned tile floor leads through to the kitchen and dining area, where a yellow and orange mural covers one wall, a surreal conglomeration of birds, plants and butterflies. My Junior Suite, Oaxaca — named after the Mexican state known for its strong indigenous culture — is warm in red and yellow. Large terracotta-coloured ceramic plates with a dark blue, swishy glaze line the wall above the sofa, offset by a circular ceiling lamp. Woven, tasselled rugs of zig-zags, diamonds and stripes grace the floor, and more lilies sit in an arched alcove like an icon. Large vaulted windows provide a view to the garden courtyard.

After waking up under the strong shower in the tiled bathroom, breakfast is a highlight: each day, the ladies in the kitchen serve up a new, fresh and original dish. I sample tangy and mildly spicy green enchiladas with chicken and cheese, drizzled in sour cream; an omelette with huitlacoche, an indigenous mushroom; and creamy potato quesadillas sprinkled with chorizo, all beautifully presented. As if that wasn’t enough, the sideboard offers fresh fruit and amazing pastries: giant churros, huge shiny croissants, and sugary buns. However, among all this style and indulgence, it’s the staff that truly make a stay at the Red Tree House perfect. They are beyond hospitable, treating guests like friends and family. They help out with beer and mezcal suggestions, planning outings, and even Mexican design knowledge.

Centro Historico: Back to the Beginning

It makes sense to kick off an exploration of Mexico City with its beginnings. The Centro Historico contains many important landmarks, surrounding the Zocalo, or ‘base’ — the main square. Wandering the colonial streets, I’m drawn in to the Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso by the temporary exhibition Rastros y Vestigios, which imagines contemporary artworks as testimonies of our current age for a hypothetical future, forgoing concerns with formalism and subjectivity to focus on topic and context. However, I’m stopped in my tracks by the colegio itself. A parquet courtyard is dominated by sculpted shrubs and tall trees. Climbing stone stairs to the next floor, Jose Clemente Orozco’s moody frescoes depict the dark side of the colonisation that produced this monumental building, offset by brightly coloured and richly textured stained glass. The exhibition path winds through the building, acting as a tour of the permanent space. Stone archways interrupt the exhibition area; I emerge at another courtyard filled with a large geometric metal sculpture by Antony Gormley, Firmament IV; and more Orozco murals line up along a hallway. It’s an ideal distillation of the way past, present and future; and social reality and art practice collide in this city.

Avoiding the crowds snaking around the ruins of the Templo Mayor, I ascend in the elevator to rooftop restaurant El Mayor, which offers a consummate view of the temple, with the Zocalo’s historical buildings — the cathedral and Palacio Nacional — visible beyond. It’s incredible to see these ruins surrounded by the other, more recent stages of the city’s history — colonial buildings, modern concrete walls, and a contemporary expo tent filling up the plaza. Returning to street level, I stroll along the Madero pedestrian mall, past crowds and Times Square-style costumed characters, from the main players of Toy Story to a gold-sequinned Death.

A detour past the House of Tiles brings me to the decadently deco Palacio de Bellas Artes, and I enjoy the adjoining Alameda Central park on my way to the Museo de Arte Popular. On entry, I’m immediately greeted by a large, colourful dragon figure, Alebrije Alfa by Ricardo Linares Garcia. Friendly and helpful staff direct me to begin my explorations at the top floor. As the elevator ascends past a ceiling of white sheets, a wide smile spreads across my face as many more bright creatures emerge, leaning over the balcony of this light and bright building.

The form was born from the hallucinatory imagination of Mexico City artisan Pedro Linares in 1936, when he dreamt of a forest of fantastical creatures, all shouting to him, “Alebrijes!” He began bringing them to life in cardboard and papier mache, then shared his techniques with family members and other artisans in Oaxaca, who continue to create alebrijes to this day. The museum emphasises the way popular art changes over time, influenced by natural and cultural forces to evolve, rather than stagnate or die off. Materials also represent Mexico’s extreme biodiversity. In the case of alebrijes, the papier mache technique has been translated to carving using Oaxacan copal wood, most notably by Manuel Jimenez. Another artist featured prominently in the museum, his work brings my mind back to the Red Tree House’s coyote. There is a definite sense of a life force in these animalistic folk works: the carved creatures exude personality.

Elsewhere in the museum, toys and other household items are grouped according to type and arranged in aesthetically pleasing displays, making art out of the everyday. I’m excited to recognise the ceramics from the wall in my suite back at the Red Tree House, this time stacked horizontally and vertically, and even in a circular fashion. Magic seeps in here, too: a tapestry featuring fairgrounds, helicopters and bedroom scenes alongside agriculture and fantastical animals is reminiscent of a Grayson Perry work. Crucifixes, nativity scenes, and altars sit in conversation with historical and contemporary devil and animal masks, while an entire room is dedicated to the Day of the Dead. Here, folk art is a tangible expression of Mexican cosmology, where lines between man and nature, and life and death blur.

I return to Condesa for dinner. La Capital’s open kitchen reveals chefs busy at work, while a blackboard above features highlights from the menu. I’m surrounded by a cacophony of conversation, emanating from romantic dinners for two and gatherings of friends. There’s a good mix here between comfort and style: irregularly hung light bulbs on long strings with shallow shades recall an art installation, while wooden tables and chairs are not flashy, but well made. Gold and silver framed mirrors hung at angles on the wall reflect the kitchen and the dining crowd, and give a colonial homey feeling. The parrilla fires up and illuminates the room in a golden glow, just for a second. I choose a crab torta with mayo and kimchi, and warmed crisps. It’s an elevated sandwich, caramelised and crunchy. Keeping this theme going, I follow up with a caramelised corn cake with carrot sauce and almond ice cream, garnished with caramel and zucchini flower. Bruleed on top, it tastes like popcorn.

Roma: Reflecting on Culture

Setting out again from the Red Tree House the following day, a stroll along tree-lined avenues brings me to the Roma district, and Galeria OMR. At the time of my visit, the gallery is showing German-Finnish artist Matti Braun’s silk paintings, which draw on a range of references, from the Silk Route to iPhone screensavers. They are meditative and hypnotic, a cross between colour field paintings and swatches on a computer paint program. Really saturated colours burn through the eyes and straight into the brain, while others provide a calming effect. Sand lining the floor — imported from Veracruz in the southeast, and as such said to reflect the displacement of people and territory — grounds the paintings, bringing an organic sense to OMR’s white cube and making me conscious of body as well as mind. I add some of the first footprints of the day.

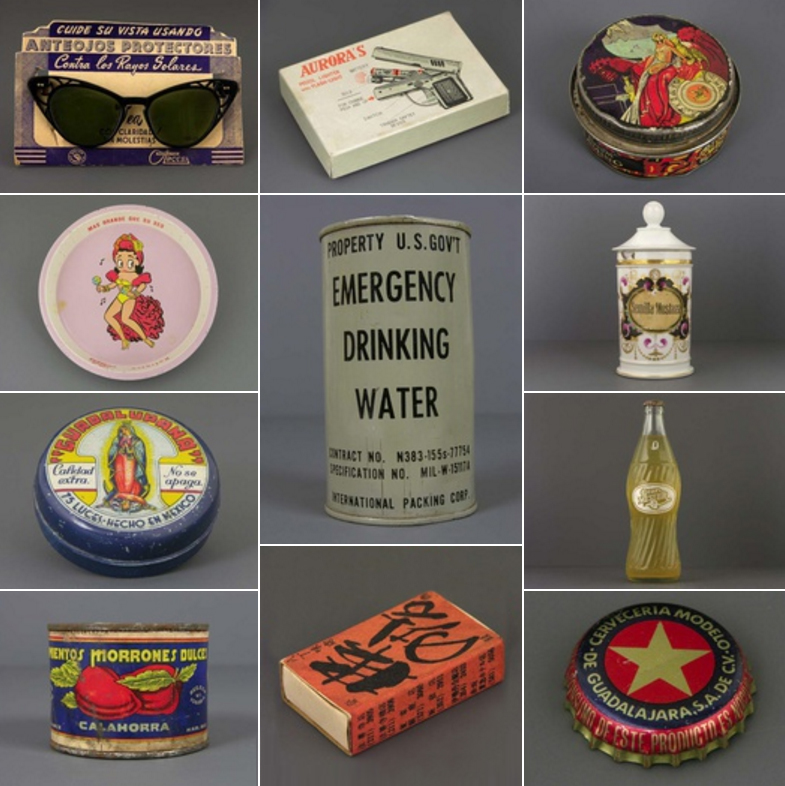

A few steps up the street is a further interesting space, the Museo del Objeto del Objeto, or MODO. The design focus of the museum is reflected in fun pink bike-shaped bike racks outside. Inside, an exhibition on eroticism through the ages contains everything from Asian, African and pre-Hispanic sculptures, old-timey personal items, and scientific developments to classic film and advertisements, Mexican art of the 20th century, and contemporary animation. In all, it’s an insightful examination of the relationships among objects and media, and social life across time.

Another short stroll brings me to the renowned Contramar for lunch. Service is next level from the get go — I’m welcomed to a table of my choice on the street, am relieved of my bag by a handy table hook, and am quickly informed of the possibility to make half orders, allowing me to try more of the restaurant’s tempting menu. Starting with some crusty, fresh bread and a gin and tonic with giant hand-cut ice cubes, it’s not long before I’m served up a plate of Contramar’s signature dish. These crispy tostadas with thinly sliced tuna, chipotle mayo, sliced onion and avocado with a squeeze of lime more than deserve their fame. A well-balanced ceviche sits in that perfect middle ground between raw and cured, and having seen the dessert tray come past, I have to try a gigantic strawberry and cream meringue. It’s a luxurious lunch, and people at nearby tables seem similarly impressed.

Chapultepec: Art in the Park

Trekking a little further this time, along leafy Paseo de la Reforma, a large curved banner introduces Museo Tamayo, where the collection of Mexican painter Rufino Tamayo’s early 20th century work contextualises and is contextualised by modern and contemporary pieces. Trees cover the grounds, even breaking through the pathway, creating a magical feeling in the middle of this large city. This is furthered by a ridiculously tame squirrel, who frolics in the grass, creeps close, and stands up, hoping for a snack. Outdoor sculptures dot the courtyard, and the strong modern lines of the museum building, all reflective glass, strike out into this whimsical landscape. The interior atrium, concrete with reflective stones, is illuminated with shafts from skylights. Ramps create sharp angles. The space opens out to the park, creating a connection between inside and outside, the material within the gallery and its location.

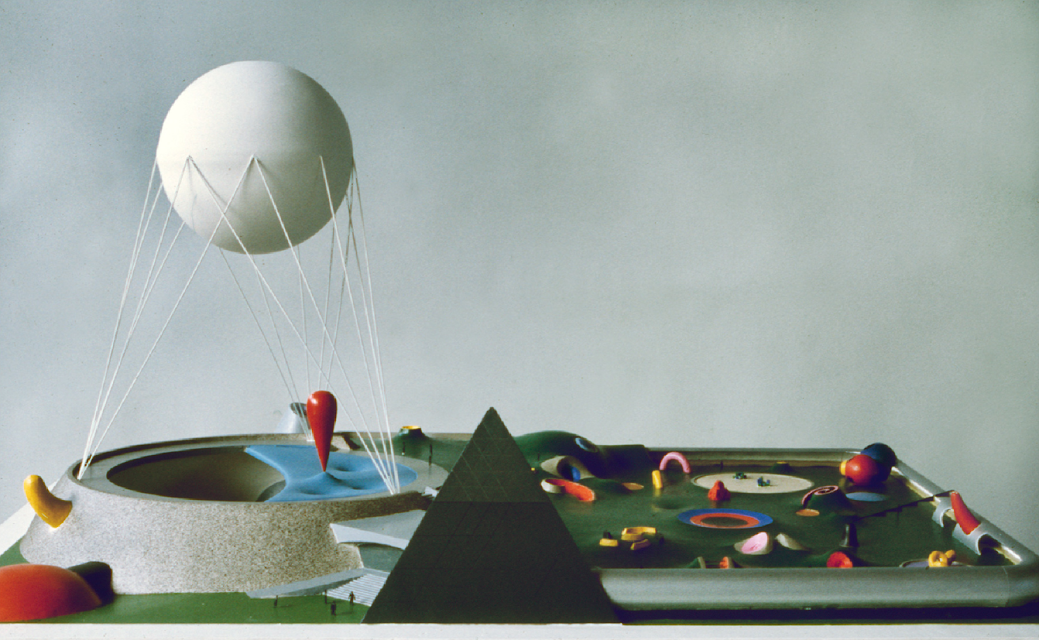

It’s an appropriate place for the temporary exhibition of artist and landscape architect Isamu Noguchi’s geometric parks, some ‘real’ and some existing only in conceptual form. Those that came to fruition are represented photographically, while marble, snow white and silver, and bronze-look models provide other perspectives. Visitors walk around the models, peering into them from different angles. The models are works of art in themselves, with Noguchi’s creations hewing closer to conceptual art than architecture, in that their effect is in their imagining as much as their concrete existence. However, it’s not all cerebral: outside, kids play on a full size version of one of Noguchi’s swing sets.

Polanco: The Opulent Neighbourhood

Further north lies the affluent suburb of Polanco, its boulevards lined with gorgeous homes and high fashion boutiques. However, I pass these by, towards more aesthetic contemplation at two huge private collections, Soumaya and Jumex. The strange concave lines and shiny snakeskin surface of the former, designed by architect Fernando Romero, is instantly recognisable. Founded by investor and philanthropist Carlos Slim in memory of his late wife, Museo Soumaya covers all official art history. I take an elevator to the top floor and make my way back down along a ramp tracing the circumference of the structure, traversing 15th century oil paintings to impressionist masterpieces and 20th century Mexican art. It’s a little historical for me, but a bright Diego Rivera mosaic, large Tamayo watermelon canvases, and the imposing and detailed Gates of Hell — one of an astounding collection of Rodin bronzes — make me glad I extended the effort.

Across the way, Jeff Koons’ Balloon Swan commands the courtyard of Museo Jumex, reflecting the surrounding architecture in its gold sheen and looking convincingly rubbery and air-filled for a stainless steel sculpture. Another temporary exhibition, a retrospective of the work of Peter Fischli and David Weiss, is spread across most of the museum. The substantial real estate of the top floor’s very, very tall walls is maximised by a photographic display, and a crowd gathers around a video work, The Way Things Go, a variation on a Rube Goldberg machine. Downstairs, Question Projections does exactly what the title suggests, with queries ranging from the philosophical and earnest to the mundane and funny covering a dark wall.

Visitors must relinquish phones and anything else on hand to visit the formidable and delicate Suddenly This Overview, a tongue in cheek ‘encyclopaedia of everything’ where sets of supposed polar opposites (Theory & Practice, Up & Down), everyday life essentials (Bread), fairy tale scenes, and imagined reactions or moments around significant historical events (Mr & Mrs Einstein Shortly After the Conception of Their Son, the Genius Albert) are sculpted of unfinished clay — pointing to the unfinishable nature of the project, while also feeling fresh. Seeing all this work gathered in one place, I get a sense of how much fun the two must have had together — and the sense of loss when one half of this partnership, Weiss, died in 2012.

Stepping outside, I’m caught in a rainstorm, and hail a cab the short distance to another of Mexico City’s must-eat restaurants: Dulce Patria, on Polanco’s main drag. Rain patters on the clear terrace roof and car horns honk in the rush hour traffic outside, but it’s calm and cosy tucked away in here. Extremely attentive service teeters on the edge of over the top. Seasonal offerings link to regions of Mexico and special events, but it’s the regular menu that draws me in with some fresh twists on classic dishes.

Chips and dip are taken to a new level: pepita-encrusted crisps seasoned with anise and lime are served on a bed of hibiscus flowers with slivers of dried plantain, apple and radish, and dried pineapple butterflies that taste like candy, with mayo and salsa for dipping. Usually an after-school snack, this dish harks back to the good old days, adding a dash of sophistication. When it comes to the esquites, a street snack traditionally enjoyed on rainy days like this, the corn is not as fresh and juicy as it could be, but it’s beautifully seasoned — and there’s no need to chase the seller’s cart down. Braving the rain again, I set off ‘home’ to the Red Tree House.

Coyoacan: Frida Kahlo’s Territory

Further moving Mexico City aesthetic experiences require a little more labour. Having heard that Casa Azul, the Frida Kahlo house museum, is jammed daily by hordes of tourists (like me), I take a proactive approach, booking a ticket online for the first viewing at 10am, and arriving well beforehand. Even so, I find a line stretching along the street from the door. Fortunately, those of us already with tickets in hand don’t languish too long, and I’m soon inside this home where so much modern art history was made. Photographs give a sense of the lives passing through the house, but it’s fleeting, as each new entrant to the house moves the last further along the viewing route.

However, a sense of intense feeling comes through in particular works on show, such as Pies, para que los quiero, si tengo alas pa volar (Feet, why do I want them when I have wings to fly), drawn shortly after the amputation of Kahlo’s gangrenous right leg, and it is memorable to stand in the kitchen, the studio, the bedroom where the artist worked, lived and died. An interesting complementary exhibit is that of Kahlo’s clothing, rediscovered in the house’s bathroom, which had been off-limits until 2004. Examination of the artist’s traditional Oaxaca-driven personal style, which has influenced designers like Jean-Paul Gaultier and Dolce & Gabbana, reveals a mix of motivations: honouring her mother, hiding her disability, appealing to Diego Rivera’s tastes, and making a political statement.

Not quite museumed-out just yet, I walk down towards the centre of Coyoacan to the Museo Nacional de Culturas Populares. A little more provincial than its counterpart in the Centro Historico, there is no English translation, but the material is well worth a look. An exhibition focusing on Oaxaca textiles hammers home the influence of the region, with pottery, embroidering, carving and other arts bringing tradition into the present. Steps away, at Corazon de Maguey, I enjoy a perfectly salmon-coloured rose, with another Oaxaca speciality, tlayudas — tostadas with black beans, shredded lettuce, cheese and chorizo.

Listening to the sounds of an organ grinder, while a fountain sprays in the background and squirrels snack in the trees, I reflect upon the surprisingly consistent theme my time in Mexico City has brought forth. The resurgence of the retro and the historical, and particularly all things Oaxaca — from the Red Tree House to the city’s museums and restaurants — indicates a revaluing of tradition, not just as a static location of a fixed identity, but as a dynamic, generative force. The exhibitions and menus may change — if this movement tells us anything, it’s that they must — but the creative undercurrent of Mexico flows on.