Pierre Frolla: An Invitation to Protect the World under Water

A world-champion freediver who considers himself half fish, half human, sheds light on freediving beyond competition, opening our eyes to an experience and environment that is anything but dangerous when treated with a little respect.

With the death of Loïc Leferme in 2007, you decided to leave the world of competitive freediving. Was it time for new challenges such as environmental advocacy, and the peace and sport movement?

I didn’t regret the choice. I had earned four world champion titles and I was more aware of my health. I had been in the hyperbaric chamber several times — maybe one more time could have been fatal. I think sharing my ideas and feelings about protecting the environment through teaching kids, young adults and through documentaries is today what makes me more happy. Freediving is not only a competition for the highest score, it is also a way of life that I love to share with people. Interacting with the wild with respect and humility.

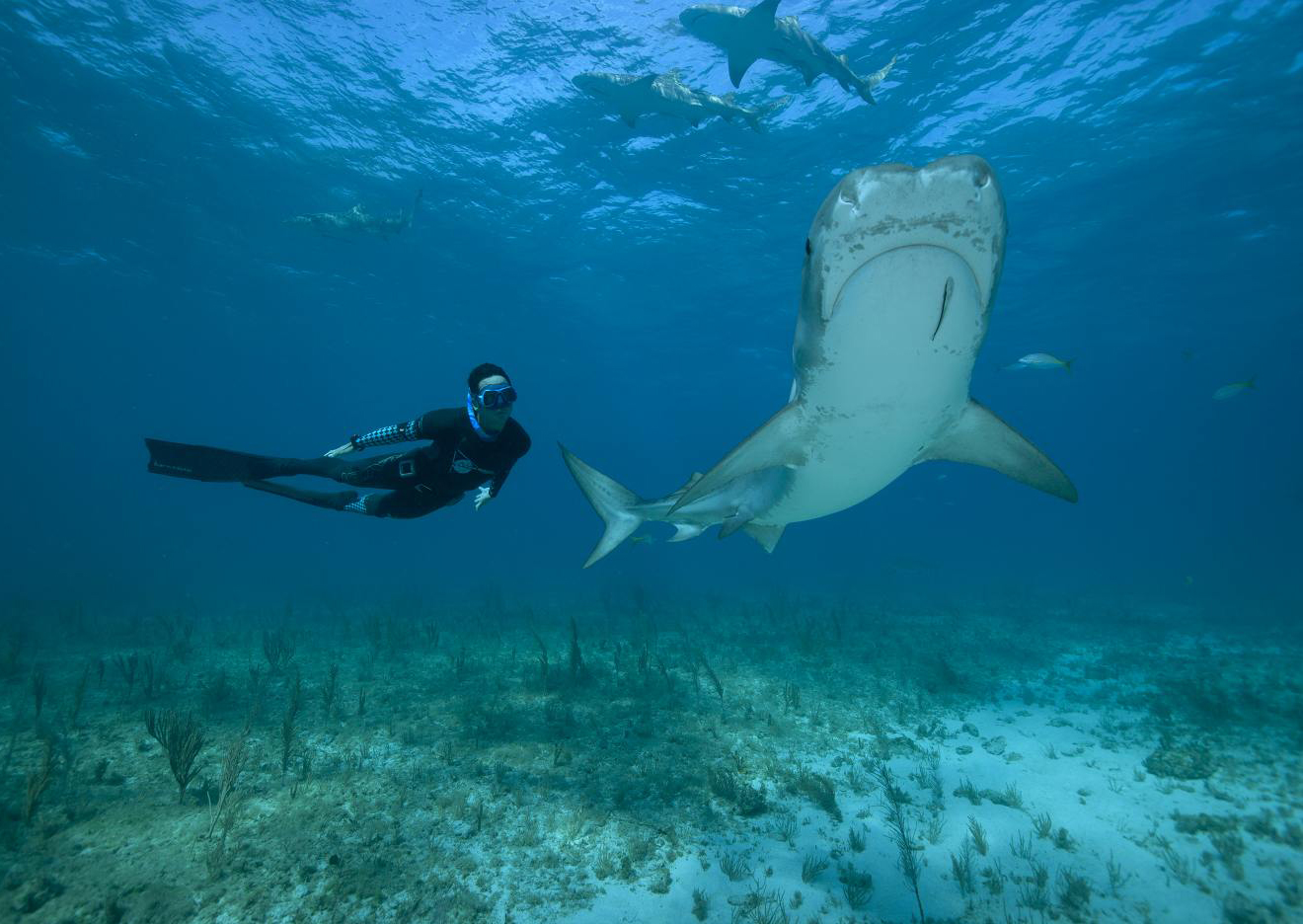

Danse with the Océan shows you frolicking with dolphins, a turtle and tiger sharks, emphasising that the ocean has become your natural playground. Have you ever felt you were you born into the wrong species?

I consider myself as half human, half fish. I am happy to have these interactions with wild animals. My interests were to overcome some fears I had with sharks, and I am showing everyone that if you respect the species underwater, you can interact with them without danger — when you understand their behaviour and respect their rules on their territories. I see myself as someone who can be invited by the wild underwater world because I show respect to what they are. I sincerely wish that everyone should have good behaviour with our environment.

How does free diving promote “communicating with one’s self” as quoted from The Peace and Sport website and what do you mean by this?

Freediving is a very intimate sport, you hear mostly your heart beating underwater, there is not much sound there. So this sport brings real introspection. You face the deep sea with only your own human ’envelope‘, you feel humble, and a tiny part of this world. This forces you to respect, to be respected; you feel free in your movements too. Freediving is often seen as a mystic sport; I do believe this is an amazing way to enter the underwater world with the least intrusion possible. You are part of it, and there is nothing more exciting than being invited to communicate and sharing simple moments with any kind of species, even predators.

In 2009, you conquered your fear of sharks by diving without protection or assistance with a 5.5 metre great white shark. What did that experience teach you?

This taught me that you can overcome your fears by facing them with professionalism. You cannot interact with a great white shark without specific behaviour. By learning how they behave, filming them and approaching them, I learnt that they are not human killers, as popular belief would have us think.

They are dangerous animals of course, and you need to stay aware of that, but they don’t particularly like human flesh and they are not killing for fun. Sharks are fearful animals most of the time and if you don’t represent a threat for them, there is no reason for them to attack. Sharks may attack when you don’t respect their territories and code of behaviour or because they confuse you with another kind of species they eat. This is why, above all, I learned how to understand them, their behaviour, show extreme respect to them; I wait for them to invite me; I introduce myself to them first and they decide if they want to interact or not. I stay conscious of my body movement at all times to show no sign of aggression. These interactions bring me an immense joy and I love to share that experience with other people.

What inspired you to establish L’École Bleue?

I think if we want to change the behaviour of the human species toward the environment, we need to teach kids and young adults how to behave underwater. Sharing with them the beauty of nature, making them more conscious of the fragility of that beauty. I also teach them not to be aggressive with animals and the impact of pollution on our underwater environment. When kids and young people dive with me… there is no word to describe the feeling when they find plastic underwater. They do understand that this is such a lack of respect for what they love. I hope that this way of sharing my passion and my philosophy of life with them will modify their future behaviour. L’École Bleue (Blue School) is a fantastic school to learn some principles of behaviour when into the wild: respect, humility and fraternity.

You grew up in Monaco, for many the home of privilege and ultra consumerism but also an ocean city. What is the conflict between the planet’s increasingly stressed environment, threatened by conspicuous consumption, and the sort of environmental values you are now promoting?

I am very active in Monaco in developing awareness about the Mediterranean Sea and the planet’s oceans. Monaco has always been conscious of the importance of ocean. Since S.A.S. Prince Albert I, Monaco has been aware of protecting the environment. As a kid, I was more underwater than at school and I have always been a strong admirer and protector of animal species.

We cannot deny that consumerism has its laws, but I am optimistic that we can find a balance between them and protecting the environment. The conflict of environmental protection, consumerism and mass production exists; it is undeniable. But I hope my work of making people conscious through communication will contribute to developing rules that fix boundaries that respect and keep our nature more protected.

You visited New Caledonia and dived at Lifou, along with other parts of the world’s second largest reef. What is special to you about this relatively little-known reef system?

A reef system is first of all a fantastic place for underwater life. In New Caledonia, my brother is a scientist and specialist in the environment. We have very good friends in the tribes that are guardians of the oceans. There, you have to tell them exactly what you are going to do in the ocean they protect before diving. They are freedivers themselves, for fishing. My brother and I have a special bond with these guys who, in some way, do what we also try to do.

Tell us more about your relationship with the Kanak people of New Caledonia; what can we learn from their culture?

The Kanak culture is very special. They don’t own land (or the ocean), they are just guardians of the land and ocean. The chief of the tribe gives to each family a piece of land to protect and they take care of it. They don’t care about possessing things. They are less materialistic than our society. Everything is shared in their community. They care a lot about customary laws called coutumes, (originally introduced by the French) where you need to declare what you are going to do in the territories they protect, then they will decide whether to allow you entry.

For my brother and I, the Kanak tribe knows exactly how much we respect their tradition and nature, and it is then a pleasure to share a good dive for fishing. Fishing might seem contradictory to environmental protection but in the Kanak tradition, you can only take from the sea what you are going to eat. This is pure respect for the food chain. No mass fishing is allowed.

Tell us about your film On A Long Breath. What inspired you and director Philippe Gérard and what do you aim to achieve through the film?

This film started after a dinner in Monaco. We both wanted to show what freediving can be, besides a competition. I wanted to show that freediving is not only what people may have seen in the widely known movie Big Blue. We began work very quickly — we met in April 2012 and started shooting in 3D underwater in August. There was no time to send a proposal to the relevant administration for funding.

I wanted to show the audience what I share all the time with people I meet and work with, to make them aware of nature through freediving. This film is for all people, including those who don’t dive. Some audience members may never dive and the film is then a nice invitation to share my world with the people who will never join the underwater world. Some buyers of the DVD have already commented that they loved the film, and I think they were not divers at all. I am happy that we have been able to find a compromise between the filming technique and the natural way of behaving in freediving. You cannot make an appointment with nature, and doing 3D underwater was quite challenging. I think the result is quite good.

Where to for Pierre Frolla from here?

I will continue to extend my efforts to make more and more people aware of the need for protection of the underwater world. I will share more adventures, learn more about wild species to understand them better and be more active in teaching kids through expanding L’École Bleue.