For the Love of Lingo

What makes us human? The quality that separates us from all other creatures ─ that is irrefutably, uniquely ‘human’ ─ is language. Language is exquisite in its properties and its potential. We use it to convey information; describe places, objects and others; to recount the past and plan the future; to emote, imagine, invent. But how did language first begin, and how did it evolve into a tool that allows us to produce potentially infinite meanings?

When we explore the ‘evolution’ of anything to do with humanity, it is impossible to do so without citing Charles Darwin and his seminal notion of the origins of species. Wildly controversial at the time, Darwin’s idea is often considered to be the most profound and powerful theory of the last 200 years, and provides the frame of reference for most discussions about who we are and how we came to be, including how language evolved. For his part, Darwin believed that language was an adaptive trait — that is, the ability to use language and communicate made humans better adapted to their environment and therefore more successful as a species.

Language, like the rest of the human condition, evolved gradually over time through the process of natural selection. This will ring a bell even for those of us who slumped through high school Biology with one eye open. Natural selection and the ‘survival of the fittest’ — that great catchphrase — work to ensure that beneficial traits are inherited by subsequent generations, making certain individuals more effective in their ability to reproduce. If an early human was a more effective communicator, this may have led to a greater hunting ability, resulting in a more reliable, consistent source of food (one of the key indicators in species’ success) and therefore a better chance of survival. Think of it as ‘survival of the linguist’.

Darwin included gesture and facial expressions in his definition of language, and noted that the ability to use sound to express thoughts and be understood by others was not unique to humans. Indeed, many animals have their own particular set of calls, gestures and facial expressions they use to communicate with each other. For example, with little trouble, we are able to distinguish between the tones of our pet pooch’s bark, from woofs of warning, to yelps of excitement. Although it has been documented that monkeys emit different noises that seem to convey a variety of meanings, and chimpanzees (our closest animal relatives) have been taught to use sign language, no animals have been able to produce language anywhere near the complexity of humans’ capabilities.

One theory suggests that humans initially vocalised by mimicking animal cries, and then accompanied these with gestures, such as pointing and waving in order to support or strengthen the meaning of their sounds. In the context of an early human’s existence, these vocalisations would have centred on hunting and food gathering, perhaps using particular sounds to represent the animals they were hunting — much in the way we now use ‘meow’ to represent a cat, or ‘moo’ to represent a cow.

An alternative view proposes that the reverse is true, and that language first began as hand gestures. Any communicative language relies on shared understanding and convention of meaning, and early human language was no different. Humans required a way to convey their thoughts to each other, and used the unique ability of hands and arms to represent spatial concepts, such as shapes and actions. For example, a manual sign might depict an object such as a tree with less ambiguity than a sound could.

Further evidence in support of this theory involves the convergence of other biological adaptations, namely bipedalism (upright walking). Proponents of this viewpoint suggest that bipedalism freed up the hands and arms to be used for gesticulation. Eventually, these gestures were in effect ‘swallowed’ so that they became gestures of the mouth, lips and tongue, manifested as vocalisations.

Certainly, hunting would have been much more effective in these circumstances — sneaking up on an animal is easier if they aren’t frightened off by the noises a hunter makes. It also seems to make sense when we think of our readiness to revert to using hand gestures when words become ineffective. Consider for a moment how we communicate with a person who doesn’t speak our language — manual gestures play a vital role in getting the message across. Or in the case of a misheard spelling of words over the telephone — an ‘s’ in place of an ‘f’ — articulatory gestures (those made by our mouths, lips and tongue) are made clearer when we can actually watch someone speak.

One of the world’s best known linguists, Noam Chomsky, agrees that language developed gradually through the process of natural selection, while also maintaining that humans have an innate ability to produce grammatical language. According to Chomsky, all humans share a ‘universal grammar’ — a set of rules that can generate the syntax of all human language — located in the brain. Chomsky believes that precisely because language works within a framework of rules, and because we can use language to express such profoundly complex ideas, there must be a neurological structure that is responsible for this ability.

Chomsky’s theory of innateness explains several phenomena. Firstly, there is the fact that, at birth, humans have the potential to learn any language — as they learn to speak, children follow grammatical rules despite being surrounded by grammatically wobbly adult speech. Language, with all its rules for word order and word endings, is just too complex to be learned by observation and imitation. Chomsky concludes that children must therefore possess some inherent knowledge of language that enables them to acquire it. Steven Pinker, another widely cited linguistic researcher, refers to this ability as ‘the language instinct’, and points to the FOXP2 gene (thought to play a role in the production of speech) as ‘the grammar gene’.

The difficulty faced by language researchers, regardless of their discipline, is that spoken language is by its very nature impermanent. Unless recorded, speech ceases to exist the moment it leaves our mouths. And this is a sticking point for all theories of language evolution — the lack of concrete, archaeological evidence to unequivocally support any theory of how language evolved. If our understanding of our biological and physiological origins is pinned to the scattered and incomplete skeletons of million-year-old species, then language — in all its ephemeral glory — is quite literally left behind.

According to archaeological evidence (fossils, to you and I), around 200,000 years ago, the first of our human ancestors emerged in Africa, and by about 100,000 years ago began to migrate. By about 60,000 years ago they left Africa, and by about 40,000 years ago they had reached Europe and Asia. Many scientists believe that this kind of migration would simply not have been possible without some system of communication; indeed, as early humans spread over the planet, their material and symbolic culture became richer. Although they disagree on the timeline specifics, most researchers do agree on one thing: that something — perhaps a number of different things — occurred to cause a shift in human brain development.

Some suggest there was a sudden genetic mutation — a DNA ‘big bang’ — that gave rise to a number of changes such as an increase in brain size and a change in neurological organisation. This increased mental capability resulted in sophisticated tool use and the creation of art, and also the ability to represent these objects through language. The ability to discuss objects, and perhaps explain how to use them, would certainly be beneficial to humans in their daily search for food, or in the increasing complexity of their social groups.

Other than the physical or biological evolution of language, there is the notion of cultural evolution, which has probably had the greatest, most recent impact in human evolution. Around 10,000 years ago, humans began to domesticate animals and develop agriculture, transitioning from a hunting and gathering lifestyle to farming. Keeping livestock and growing plants to harvest ensured that human existence became more static, and people began to live in larger communities that could be supported by these plentiful and reliable food sources. With the development of farming, communities began to spread further afield, acquiring more land to farm in order to sustain larger populations. It is thought that early humans would have required a more developed form of communication in order to organise trade and

resolve disputes.

But how have we ended up with the 6000 languages (or thereabouts) we have presently? Many scholars have likened the development of a multitude of languages to evolutionary theory: the process of species evolution is analogous to an enormous tree, with multiple branches, multiple twigs and multiple leaves. Just as species split off to form new species, languages split to form dialects and completely new languages. Similar to the way the common ancestor of all mammals gave rise to the whale, the horse and the orangutan, early (or ‘proto’) languages serve as the common ancestor for the thousands of languages we hear in the world today — the trunk of the linguistic tree, so to speak.

For example, the main language groups of Europe such as Germanic (comprising English, German, and the Scandinavian languages, including Icelandic), Slavonic (comprising Russian, Polish, Czech and several others used in Eastern Europe) and Italic (comprising Latin and the Romance languages of Italian, French, Spanish and Portuguese), are members of a larger branch of the linguistic tree, known as the Indo-European languages. Other twigs on the Indo-European branch include Greek, the Baltic languages, the Celtic languages (Welsh, and Irish and Scottish Gaelic), Farsi, and even the Indian languages of Sanskrit and Hindi.

It has been suggested that these languages all evolved from what linguists call Proto-Indo-European, the evolutionary common ancestor of many of the languages of the northern hemisphere. Evolutionary psychologist Quentin Atkinson has combined strategies from population genetics and linguistics to attempt to trace the origins of language by applying the concept of the ‘founder effect’, whereby genetic diversity is decreased when a small population breaks off from a larger one, as not all the genes are carried with the smaller group. Atkinson argues that “The same scenario can apply to elements of language, including phonemes… the sounds that each language uses to make up words.”

Noting that biologists have used the correlation of decreasing genetic diversity with increasing distance from Africa to support the idea of an African genetic origin for humans, looking at the number of phonemes used by various languages throughout the world he found “a clear decrease in [linguistic] diversity with distance from Africa… [which] suggests that like our genetic ancestry, our language ancestry can be traced back to a single origin in Africa.”

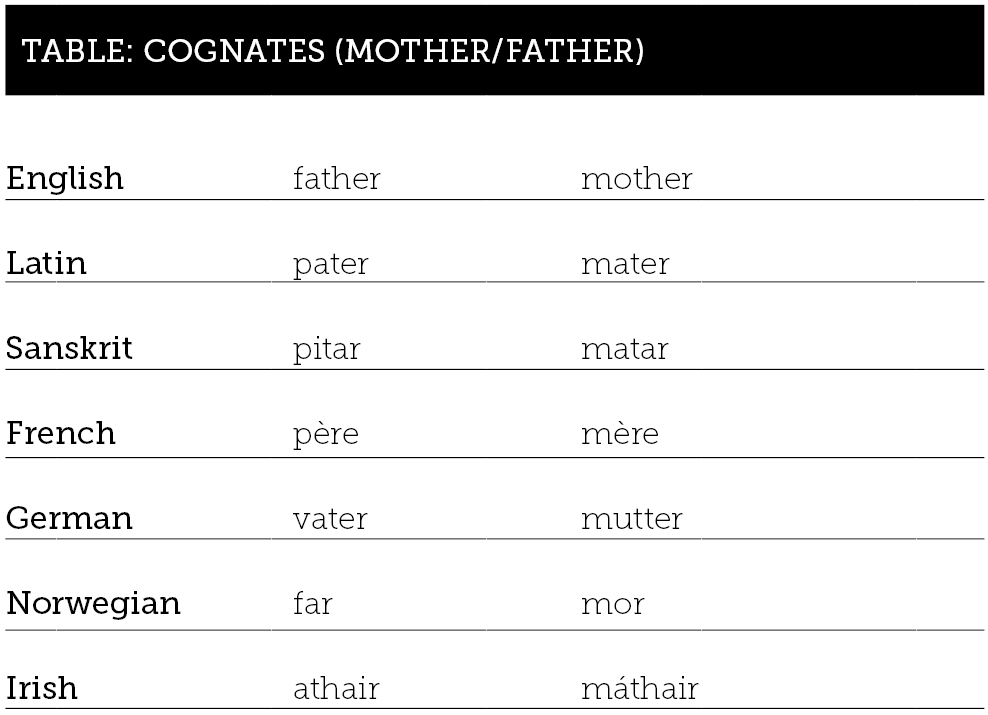

Another way in which linguistic researchers can explore the evolutionary roots of languages, is to study ‘cognates’ — words that are etymologically related (see Table below). Derived from the Latin cognatus, meaning ‘blood relative’, cognates are useful because they allow researchers to explore the similarities and differences between languages, based on knowledge of their origins. Language researchers consider the existence of cognates as evidence of today’s languages having the same common ancestor, much like all humans are descended from one common ‘ape’ ancestor.

One suggestion is that our linguistic antecedents evolved into the many languages of today in a process similar to dialectal variation. A form of communication is often defined as being a language if there are two or more people that are able to communicate and be understood by each other. When two forms of communication are so different that it is impossible to establish an understanding, then they are regarded as two separate languages. However, it can be the case that two speakers of the same defined language have difficulty in understanding one another — for example, there are many varieties of English, and a speaker of American English may find a Londoner incomprehensible.

This is often due to dialect forms of the same language. This is one explanation for the existence of thousands of different languages — that they evolved due to groups of people migrating, settling, and becoming geographically isolated from other groups. Eventually, their forms of speech changed in pronunciation, structure and word meaning. It is thought that this dialectal variation continued until these forms of communication became distinct languages in their own right.

However, another argument stems from the idea of creolisation. In the recent past — during the days of colonial expansion — traders and colonisers developed a form of language, called a ‘pidgin’, in order to be able to communicate with indigenous people. Pidgin languages have very little or no grammar, but were effective in the exchange of simple ideas. Pidgins can develop in complexity and over generations can become more sophisticated creole languages, which do have grammatical ‘rules’.

There is disagreement between linguists as to whether creoles are truly distinct languages, or whether they might just be dialects — but their existence may explain how different languages have developed. Indeed, that people of differing races and cultures are able to ‘create’ a language in which they can successfully communicate is the flipside to the exclusivity of dialectical development, and may also add weight to the idea of a ‘hard-wired’ or innate grammatical ability, as Chomsky has maintained.

All this might bring new meaning to our understanding of what it means to be a human: we all use language to detail our daily lives, to express our experiences, to explain our emotions. If, as the current body of scientific evidence suggests, we are all descended from a common ancestor, then we are not as different as we might believe. And if we search for common ground, perhaps it is best to search for that which represents the ideas we all share — then we will stand a greater chance of communicating effectively. When one considers that all humans are born of a mother and a father, and that our words for these concepts are linguistic ‘blood relatives’, it makes one question whether our languages, rather than separating us, actually unite us.