Simon Beck and the Art of Snowcraft

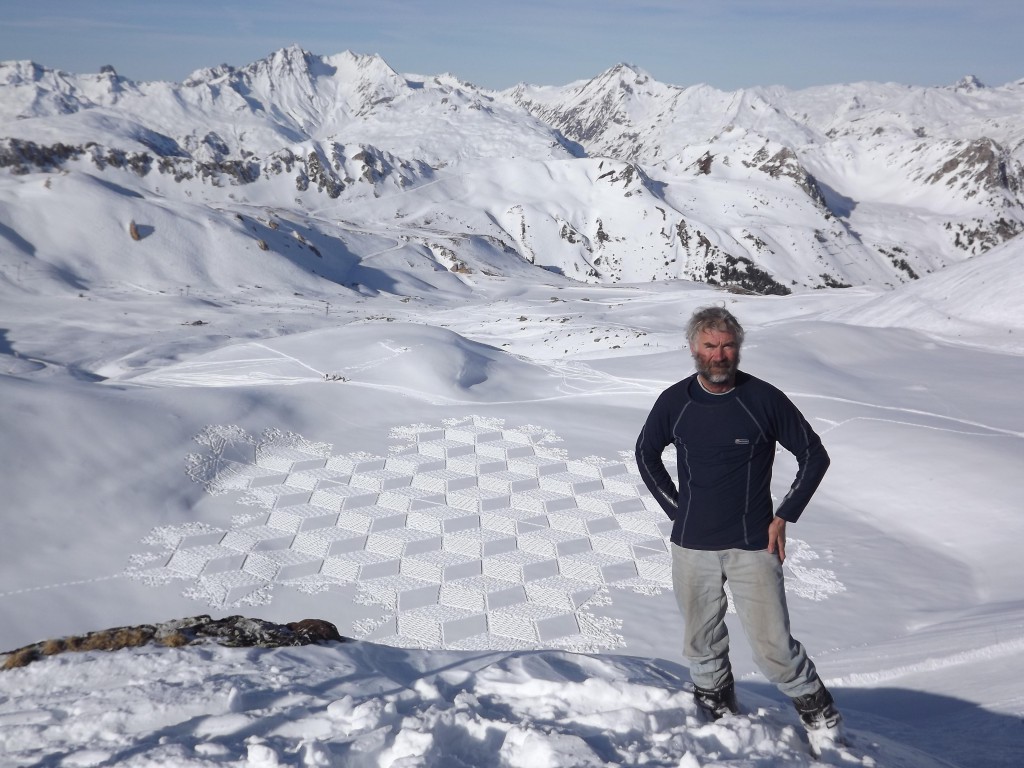

Beck’s working relationship with snow began when he bought an apartment in Arc2000, a ski resort in France. He recalls that when the ski lifts closed “one fine day in December 2004,” he found that he had “both time and energy to spare,” and his craft developed from there.

Beck works tirelessly to create large-scale patterns in the snow, the majority of which are made up of his popular symmetrical geometrical designs. The Koch snowflake is one of his favourites because, he says matter-of-factly, “it is easy to make and makes good use of a circular area.” Beck is open to the possibility of creating more ‘organic’ drawings, however, and emphasises the need to keep his patterns fresh, as drawing the same ones repeatedly can become monotonous for both artist and viewer.

Due to the visual impact of the designs, it would be easy to conclude that there is a profound meaning within the work — but Beck maintains, “there is no deep message.” Some of his drawings are accompanied by slogans, such as ‘Protect Our Winters’, and others contain hidden codes which the artist does not elaborate upon. However, the main purpose of the designs is aesthetic.

Because of the nature of Beck’s work, a fair amount of planning goes into these designs. There is no chance of making it up as he goes, and there isn’t a lot of flexibility to change one’s mind once in the middle of a snow creation, as this can become “a bit of a minefield.” Thorough planning results in less time spent in the field, with the added bonus that when “the brain work” is done he can have a much more pleasant time listening to music and enjoying the process. This methodical approach, eliminating unnecessary time-wasting, is crucial when one considers how long it takes to bring some of these designs to life: Beck’s most complex creation to date took him 32 hours in the field to complete.

Beck also works with sand to create his art, and notes the advantages of the medium’s pleasant texture, the often-sunny working environment and the possibility to measure out a design without leaving tracks. However, his connection to the snow is not dampened by his work with other mediums: he maintains that not only does snow art look better, but a small amount of unwanted snow or rainfall does not do significant damage to the drawing and there is no time limit to complete it. Further, as no one else is making snow art, working in snow is a more lucrative field.

Beck generally works alone, as it is difficult for others to commit to a shifting schedule caused by ever-changing weather. With plenty of skiers around to communicate with as he works, though, he doesn’t find it too lonely. When the ski fields have closed for the day and he is working alone on the final phase of his drawing — the shading — Beck puts on his music and is “pretty well wrapped up in [his] own little world.” Content with this process, Beck appreciates each step’s importance in the realisation of such grand-scale pieces of art.

The artist has been commissioned to work in a number of exciting destinations, but one of his favourites is a familiar one: the Lac Marylou at Arc2000, “an outstandingly good site as it is exactly the right size.” He also makes note of the places that are ideal but perhaps more difficult to work with alone, such as the super lake at Verbier, which would require “a whole team of about 10 people (preferably marathon runners) to make good use of it.”

On his wish list of other mountainous destinations, Beck says that he would aim for those where spectacular and well-known mountains could be incorporated into the photographic documentation of the drawing, such as Patagonia, Alaska, the Himalayas and Yosemite. He is also interested in working urban locations, including Central Park in New York, the open spaces around Salisbury Plain and Christchurch Meadow in the UK, and Moscow’s Red Square. However, with these places “clearly one would need a lot of luck to be in the right place at the right time.”

Beck stays in Arc2000 except when he is asked to go somewhere else to create new artworks, which is happening more often as word of his talent spreads. Apart from his commissioned drawings, Beck takes all of the photographs of his art himself, having learned quickly the ideal locations and times of day to document the work. Though he gets hounded for video documentation, he prefers to keep it simple, observing that he is “apparently out of step… in preferring high quality, non-moving photography.”

Beck has also been involved in a corporate collaboration with Icebreaker, wherein his designs were reinterpreted by the company’s graphics team for placement on the company’s merino wool clothing — perfect for snowy environments. For Beck, Icebreaker was an attractive company to work with as “they are built of the right kind of people who care about the environment and hike up mountains and go trail running and make the effort to see that the animals are well cared for.”

Beck is careful to treat his snow canvas with care. Some of the proceeds from his collaboration with Icebreaker will go to Protect Our Winters, a group dedicated to fighting climate change. In relation to this issue, he notes that climate change would eliminate some potential sites for his art, but he is optimistic, adding that “there remain ample venues high enough” that they are not affected. Beck’s exquisite but temporary pieces of art, created using only natural sources, are such valuable expressions of a rare skill. Here’s hoping that he always has an abundance of snow at his feet.