The Cognac Generation

With a whoosh of hydraulics and a whine of turbines, our high-speed train from Paris’ Charles de Gaulle International Airport slips into the humble Cognac train station, a bustling place of tourists and locals eyeing departure boards and collecting luggage. There is that lovely laid back ambience of rural France, where nothing happens fast and no one seems to mind.

We mount up into a convoy of sleek Mercedes vans and delve into the idyllic countryside. On either side of the road are farms with rustic cottages, copses of tall trees, and vineyards that run towards the horizon. We pass tractors hauling silage and clutches of school children in immaculate white uniforms. Soon, we’re surrounded by vineyards punctuated only occasionally by red-roofed farm houses and small batch distilleries. It doesn’t take long to figure out what binds many of Cognac’s 35,000 inhabitants.

On the main roads out of town there are billboards for cognac tasting halls at every junction. All the major brands have dedicated visitor centres where cognac lovers from across the world can indulge in their passion and even purchase a rare drop for loved ones back home (or their own private stash). Thanks to great train access from Paris and its international airport, tens of thousands of travellers visit Cognac each year on whirlwind tours that often include several European capitals, along with other iconic locales like nearby Bordeaux, Burgundy and Champagne.

For many travellers it’s a grass roots education and a chance for major cognac brands like Martell, whose distillery and vineyards we first visit, to extoll their rich heritages and artisanal production. Cognac is essentially brandy — distilled wine spirit called eau de vie that’s then aged in wood barrels. The major difference is that only brandy made in this picturesque corner of the world, nestled on the banks of the Charente River 400 kilometres southwest of Paris, can be called ‘cognac’, thanks to strict quality controls and the French appellation d’origine contrôlée certification that protects specific products from a specific geographic region.

After lunch and a tasting tutorial in the shadow of towering copper stills at one of Martell’s main plants, we return to town, the sun above periodically breaking through low-hung clouds to douse the rural setting in vibrant colours. Many fellow visitors to Cognac can be seen walking its streets under the mid-morning sunshine, gazing up at the ramshackle collection of 15th to 17th century village homes that huddle around a main cobblestone square. They pose for photos before the Romanesque church of St. Léger and the sprawling Château de Cognac, the birthplace of the 16th-century King François I, and delve into the Musée des Arts du Cognac, a museum dedicated to the region’s single largest export.

Instead, I head down the road towards a bold blue sign that stands above weathered stone walls. At the Martell visitor centre, housed in the brand’s former distillery, 90-minute tours are conducted in several languages, explaining the painstaking production process to travellers from across the globe — some of whom are true connoisseurs, and some who perhaps only know the luxury attributed to cognac without knowing how it’s made, or understanding its subtleties.

It seems fitting that the oldest of Cognac’s great houses was also founded by a visitor looking to indulge his passion and create a legacy in the process. In 1715, Jean Martell, a young merchant from Jersey, journeyed to Cognac to try his hand at producing the spirit that was so beloved by the British at the time. Cognac, which stretches over two regions in western France — Charente-Maritime (bordering the Atlantic Ocean) and Charente (a little further inland) — had been producing wine since the 1st century but didn’t make eau de vie until Dutch settlers began distilling their vino in the 16th century so that it would last the long journeys across Europe.

Jean Martell worked closely with small eau de vie producers in the region’s six crus, or growth areas, to select, age and blend these colourless spirits to create the first exceptional cognacs. After his death in 1753, his widow and sons continued the tradition, eventually capturing the British market by 1814, and exporting their first bottles to China, Hong Kong and Japan in 1861.

Jean Martell’s journey from Jersey to Cognac was the inspiration for five stunning new cognacs — including the limited edition and much-coveted Martell Premier Voyage — created by cellar master Benoît Fil to mark the house’s 300th anniversary in 2015. Using 18 eau de vies from the same producers Jean Martell had worked with so closely, Fil was able to make a unique cognac that truly captured the Martell essence 3 centuries later.

Three hundred years is no small feat and the pinnacle of this monumental milestone was a star-studded party held at the Palace of Versailles, a landmark Martell has close ties with: its former resident, Louis XIV, the Sun King, was a patron of Jean Martell’s cognac and a symbol of France’s golden age, and the cognac house continues to support on-going preservation projects at the Palace.

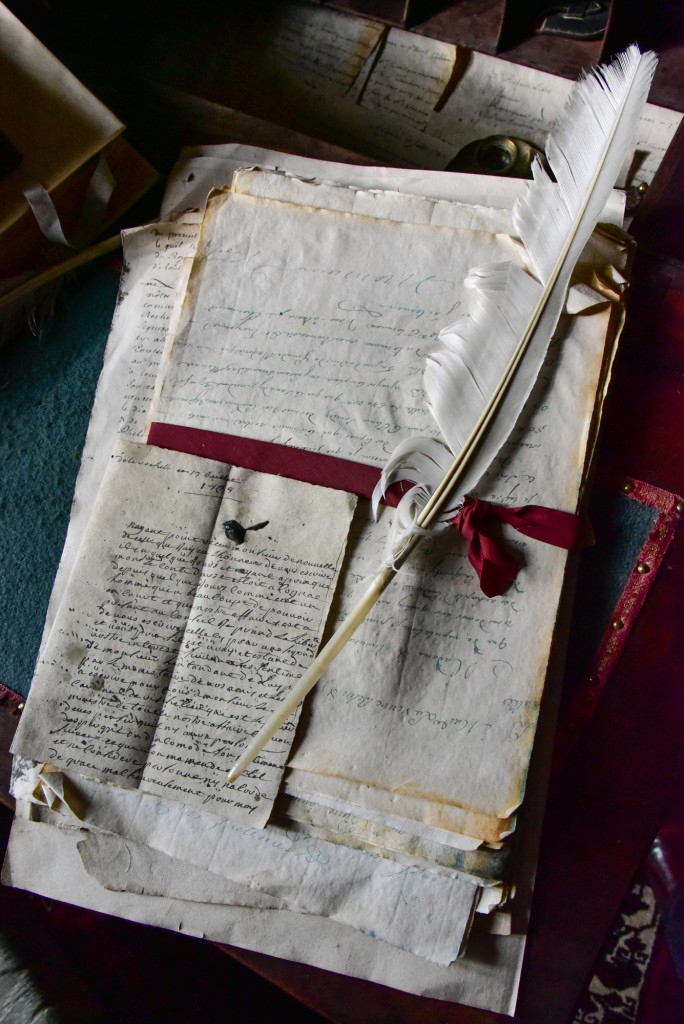

When he wasn’t making cognac, Jean Martell was clearly into record-keeping, as I discover with a behind-the-scenes peek at the house’s extensive archives — all five kilometres of them. The Martell visitor centre is actually wreathed around Martell’s original stone house, which has been preserved as a museum that can be toured by prior booking. Here, the hidden archives are the realm of resident archivist Geraldine Galland, who is slowly working her way through the extensive collection of log books, bills of sale and loading, invoices and letters dating back as far as Jean Martell’s first days in Cognac.

Touring the archives, I come across thick journals with Jean Martell’s signature at the base, and a beautifully preserved but time-weathered poster advertising cognac in China, to coincide with the first shipments to Shanghai in 1861. After 300 years of production, Martell is now available in 130 countries, and all that history is here in extensive, protected collections.

That evening we’re lucky enough to experience another aspect of Martell’s lingering legacy, with dinner at Château de Chanteloup, Martell’s stunning manor in the Cognac countryside. The countryside of Cognac is dotted with grand old homes like this, many of which are now boutique hotels and B&Bs that welcome tourists looking to learn more about Cognac and its rich history.

Acquired by Theodore Martell in 1838, and re-built in the Norman style in 1930 by then-owner Maurice Firino-Martell, Château de Chanteloup acts as an exclusive guest house for Martell’s top customers, and epitomises the tradition, elegance and sophistication of Martell’s blends to a tee. The manor house is set within 147 hectares of manicured lawns, gardens, vineyards and forests and home to a resident deer population.

On this beautiful summer evening it’s all ours, as our group, representing all the great cognac markets of the world — some of which didn’t even exist in Jean Martell’s day — dine on a menu of modern French dishes in a light-filled marquee. As the light fades and the deer peek from their glades, we toast to Cognac’s rich history, its bright future, and the characters like Jean Martell that made it all possible.