Images from a Warming Planet: Interview with Ashley Cooper

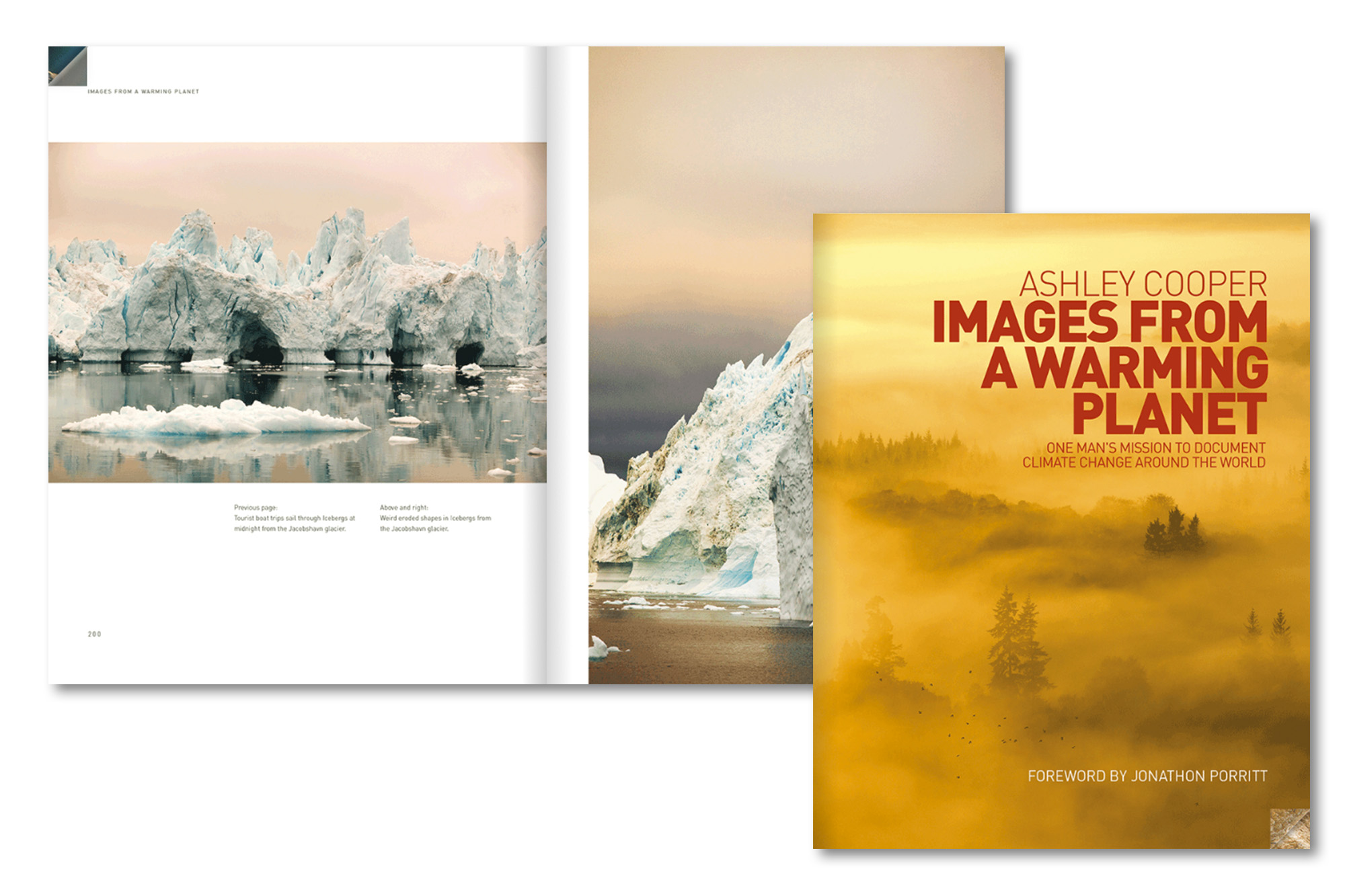

Ashley Cooper is more than a photographer — he’s a humanist, environmentalist and campaigner whose 13-year journey capturing the effects of climate change in more than 33 countries has been documented in a photographic art book entitled Images of a Warming Planet. In an interview with Destinations Magazine’s Tim Wakely, the British photographer discusses his decision to document humanity’s biggest environmental threat.

Did you always set out to become a photographer?

No, it started out as a hobby. I’ve always been into the natural world; I was at university and saw photography as a way to document my outdoor activities, like caving, hiking and cycling. I started to make a few sales out of it and thought it would be an interesting way to earn a living.

What led you to fly from the UK to Alaska and start shooting the effect global warming was having back in the world in 2004?

After I left university I established myself as a nature and wildlife photographer. In my twenties I started reading quite a bit of science material and was coming across a lot of literature on climate change. I had also read High Tide: The Truth about our Climate by Mark Lyans, a journalist who, a couple of years beforehand, had travelled to various points around the globe investigating climate change. Alaska was one of the places he had investigated. The driver for me to go there was because I wanted to look at Alaska from a photographer’s point of view — and return with some photographic evidence of climate change. I spent a month in Alaska and six days with a small Inuit community on Shishmaref Island, eight kilometres off the mainland.

Your pictures have been used by World Wide Fund for Nature (WWFN) and other high profile groups. What is your relationship like with these organisations?

The photo project in Alaska started off being entirely self-funded on the back of my image sales. When WWFN came on board as a partner, it gave me enough money to finish the project, and in turn I shared my images with them. Without their support I would have struggled to finance the Shishmaref project solely on the back of image sales.

What motivated you to continue documenting climate change after you returned from Alaska?

I was shooting a number of environmental projects when the Shishmaref Island project came up. At the time, I was searching for a direction for my work, I wanted to concentrate on one particular area of photography. While I was in Alaska I captured permafrost melt, glacial retreat and increased forest fire incidents, all of which were affecting the Inuit community on Shishmaref. I was blown away by how in your face global warming is, especially in the Arctic. I came back to the UK utterly convinced of the enormity of the issue and thought to myself, “This is what I should be concentrating on.”

Did you ever think that it would become a 13-year journey?

I’m surprised and overwhelmed by the level of support I have received for my work. Climate change is an issue people are starting to take more seriously; you don’t need to be a scientist to realise extreme weather events are becoming more frequent. Seeing the effects of climate change through the eyes of communities like those of Shishmaref inspired me to continue on with the project. They’re the people most affected by climate change — a problem they didn’t create.

You’ve led a successful crowd-funding campaign to turn 500 of your best photographs into a one-of-a-kind photographic art book. How does that feel?

It feels amazing to finally have the book published. With the project being crowd funded, people have not only believed in the project, but have also put their money behind it — making it extra special. I even had a complete stranger donate US$20,000 following a TV appearance to promote the project, which was amazing.

Never could I have imagined this project would have received so much support, let alone led to so many incredible experiences. People are beginning to think to themselves, “If we don’t do anything, things could change quite rapidly for humanity.” — an ethos this book reflects.

Are there any images you would single out as being particularly significant?

The image I am known most for, the dead polar bear on Svalbard [an island north of Norway], is an image that stands out. It was the first time you could say with a degree of confidence that a polar bear had died as a result of climate change. We got in contact with the Norwegian Polar Institute [a branch of the Norwegian Ministry of Environment which monitors polar bears in Antarctica and the Arctic], who had collared the bear. They told us the bear had lived its whole life on the southern part of the island. We found it 800 kilometres north of its hunting ground — where there was no sea ice. Polar bears only hunt on sea ice; without it they starve. The bear was all skin and bone when I found it. The image of the polar bear exploded in the media and was picked up by major news organisations all around the world including The Guardian, BBC, NBC and Al Jazeera.

What were some of the challenges you faced during your years as a climate change photographer?

Challenges came in different forms. Working in remote environments and getting to some of the places was very difficult. Climbing above 4000 metres in the Southern Alps to investigate permafrost melt came with its own potential risks. For example, the route I took to climb Mont Blanc massif is no longer used, as it’s deemed too dangerous due to the high number of rock falls. There are objective dangers to be aware of too, like when I came close to falling down a crevasse on the Greenland ice sheet. I took one step forward and my leg just sank into the void. Luckily I was able to quickly move myself backwards; I have no idea how deep it was, I don’t really want to think about it.

The most challenging aspects weren’t the physical dangers, but the human ones. In China I was approached by the army and it was very, very scary. I was in the midst of lining up a shot that showed a coal-mining factory in the background and an army barracks — with solar panels attached to the side of it — in the foreground. It was a really nice contrast. Renewable energy on one side and this awful coal station in the background. They [the army] saw me taking photos, arrested me, and took me inside.

What motivated you to continue on in the face of this kind of opposition?

Just the fact that the evidence is so glaringly obvious. I have probably seen more cases of climate change than any other human being. It has the potential to create so much havoc — that’s what motivated me to carry on with it.

Besides Images from a Warming Planet, what other projects or works are you most proud of?

I’m proud of the work I have done for the NSPCC in the UK (National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children). Working for the charity for 20 years, I’ve helped them raise £4,000,000, which has gone towards building a number of child protection units. Also working for three months with Lepra [The British Leprosy Relief Association] in Malawi, 30 years ago, is another project I am proud of. I was really blown away by their work and wanted to help them raise some money. I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do, but being a keen mountaineer and walker I came up with this harebrained plan to be the first person to climb every 3000-foot peak in Great Britain and Ireland in one continuous expedition. It took me 111 days to complete. I climbed over 150 kilometres and walked 2250 kilometres, raising £14,000 for the organisation. About 1400 people were helped with the money; it only cost £10 at the time to cure someone with leprosy. I’ve also had the opportunity to shoot well-known figures like Bill Clinton and Phil Collins, but I have to say those opportunities seem rather meaningless compared to communicating the climate change message.

What has your experience taught you?

I’ve learned to be self-reliant and resilient, to take all the hard knocks, and the rest of it. Having seen what I have seen, I have learned so much about climate change and plan to spend the rest of my life documenting it. Overall, it has been a huge privilege to go to these places and spend time with a number of communities. I am incredibly grateful for the opportunities it has provided me.

What’s next for you?

Going forward I would like to continue spreading the environmental message as well as exhibit my images around the world. I can’t see myself doing anything else except for communicating the message of climate change through photography.