The warm welcome from assembled guides dressed, as many Bhutanese still do, in pristine national costume, brings colour back to the faces of air travellers who have just experienced one of the most nail-biting landings on the planet; only 12 pilots in the world are certified to fly into Bhutan, with planes required to undertake some serious last-minute manoeuvres as they cruise the length of the valley, brightly painted houses whipping past on either side, before braking hard upon touchdown.

It’s my first visit to Bhutan, although the remote Himalayan kingdom has been on my personal bucket list for a decade. I’ve always been, like many other intrepid travellers, intrigued by a destination that has remained so well fortified against the onslaught of modernity; that has retained an ancient (and well loved) monarchy; and which measures its progress not in dollar signs or market points, but by happiness, literally.

Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness index, a measurement of the collective contentment of the kingdom’s 740,000 citizens, is a remarkably progressive approach for a country named for a thunder dragon. Coined in 1972 by Bhutan’s fourth king, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, the idea has evolved into a socio-economic development model recognized by the UN. Although Bhutan is often mislabeled as the happiest country on the planet because of the index (officially in 2016 that was Denmark), it’s certainly a land of smiles, and one welcoming an ever-increasing number of well-heeled travellers who cling to their airplane armrests in pursuit of their own little slice of Himalayan harmony.

Since 2008 COMO Hotels & Resorts has been catering to wealthy adventurers arriving in Bhutan. The company’s two luxurious lodges — COMO Uma Paro, located minutes from the airport, and COMO Uma Punakha, a three-hour drive away in a neighbouring valley — marry the best of traditional Bhutanese architecture and hospitality to create homestead-style havens that are part alpine lodge, part wellness retreat. Combining both properties and capturing the very best Bhutan has to offer, the ground-breaking new COMO Uma Bhutan Scenic Heli-Adventure is a six-night itinerary laced with world-class spa cuisine, guided tours, and a pair of the most captivating helicopter flights on the planet, and promises to offer new insight into this remarkably happy destination.

Within minutes of arriving in the kingdom I’m checking in at COMO Uma Paro, an intimate 29-room retreat that, like virtually everything in this vertiginous nation, is perched on the side of a steep hill. Here’s it’s very easy to be happy; there are roaring fires, comfy beds, and shy but attentive staff dressed in elegant, silken kira dresses. There’s the COMO Shambala Retreat, home to Bhutanese-inspired massages and an indoor pool; and Bukhari, a signature restaurant that serves hand-ground buckwheat noodles, yak dumplings, and COMO’s iconic juice blends, making eating healthy surprisingly easy.

With its wreath of mountains, dusk arrives rapidly in the Paro Valley and there’s just enough time to watch the colour sap from the towering white-washed walls of the nearby Rinpung Dzong, a 300-year-old Bhutanese fort that overlooks the town of Paro, wisps of wood smoke drifting up from homes and dancing on the cooling breeze, the first stars already slipping from cover above. Shade fills the valley like the waters of a rushing river and darkness quickly engulfs the kingdom at the top of the world.

In turn, light floods the valley again the next morning in a much happier effect that brings to life the green mountain flanks, robin’s egg skies, and honey-hued winter paddies far below. After a breakfast of quinoa porridge with almonds and apple, served beside Bukhari’s namesake fireplace, my personal guide, our driver and I depart COMO Uma Paro, bound first for Bhutan’s pint-sized capital, Thimpu, and Punakha, across the 3000-metre Dochula Pass.

The valley below is abuzz with first light. Ponies with shimmering chestnut coats wander the narrow lane down the mountain, and novice monks wrap their crimson robes tighter to ward off the last of the night’s chill as they cross the pale aqua Paro Chhu, an alpine river that flows down the centre of the valley. The winding road that reaches the capital clings to rocky cliffsides as it passes the confluence of the Paro and Thimphu Rivers. Prayer flags jitter above the rushing waters and wrap like vines along the arches of traditional bridges which leap the chasm below.

Thimphu is serene little capital city. Nestled on the west bank of the Thimphu Chuu, the world’s third highest capital is laid out north to south, with an ornate clock tower at its centre. Nearby a police officer, resplendent in his uniform and white gloves, directs traffic from a tiny hut decorated in bold reds and yellows. Bhutan has worked hard to improve its infrastructure, but when the country’s first traffic light was hoisted at the same intersection, so many accidents occurred that it was quietly lowered again that very evening. I guess happiness is sometimes not changing something that isn’t broken.

The quiet of the capital is only interrupted by the cries from the sports field, where the national sport of archery is the biggest ticket in town every weekend. It’s a curious tournament; opposing teams strictly adorned in national dress, crowd in front of the tiny bullseye, while the archers of the competing team sight their shot some 150 metres down the field. There’s plenty of friendly jostling and challenges bellowed the length of the spectator-lined paddock in an attempt to distract the archer, and when the arrow is loosened, all eyes turn to the skies, the bolt streaking through the sunshine and landing steps from the leaping revelers. A missed shot is met with more bellowed but surprisingly polite commentary, or kha shed, itself considered a complex art form, but a successful strike leads to a respectful, traditional dance that blesses the target and acknowledges the talents of the archer. Despite the competitiveness of this timeless activity, there are smiles, singing and dancing at both ends of the field, as skills are praised, arrows bestowed, and friendly rivalries stoked, perhaps with more than a few drops of local ara rice wine.

Atop the Dochula Pass I visit the solemn Druk Wangyal Chortens, a memorial of 108 stupas dedicated to those who fell ousting Assamese rebels in one of Bhutan’s few armed conflicts. With the mighty Himalayas, punctuated by Bhutan’s highest peak, Gangkar Puensum, as a stunning, sun-kissed backdrop, the memorial to the fallen — both soldiers and rebels — marks the importance placed by the people of Bhutan on life, peace and happiness.

We descend through dense forest into the lush Punakha Valley, winding through tiny hamlets and past farms where water buffalo plough the fields in preparation for spring, arriving at beautiful COMO Uma Punakha as the light begins to drain from the sky. My guest room, one of 11, including two sumptuous villas, looks north down the valley towards towering peaks, the meandering Mo Chu river winding its way through emerald rice paddies below. There’s a king-sized bed, sheesham-wood furniture, and a deep soak tub that’s perfect for frosty Punakha nights. I wrap up warm and join fellow guests on the terrace for cocktails, served under a mesmerizing canopy of stars, followed by a Bhutanese feast in the restaurant. The experience is nothing short of magical.

The next morning my guide and I step back in time with a visit to Punakha Dzong, the valley’s ancient fortress, which dates from 1637. Pungtang Dechen Photrang Dzong, or ‘the palace of great happiness’ houses sacred Buddhist relics but the monks that call it home still welcome visitors and leave us to roam its vast inner courtyards unhindered.

It’s a special day to be in Punakha; Trulku Jigme Chhoedra, the present Je Khenpo or religious leader, is visiting, and the fields that line the confluence of the Pho Chhu (father) and Mo Chhu (mother) rivers beyond the fortress are alive with colour. There are monks swathed in terracotta and tangerine kasayas; elders from the mountain villages in black ghos with white shawls and matching whiskers; giggling novices with brilliantly red robes and freshly shaved heads; and wizened old women wrapped in silk scarfs every colour of the rainbow. It’s a family affair and saucer-eyed children ride the backs of their parents and grandparents as monks recite scripture in a sing-song tempo. Everywhere there is laughter and conversation, and despite our small group being the only foreigners out of thousands of worshippers, we’re made to feel welcome.

From the past, we leap to the future the next morning as we rattle down the dusty road from COMO Uma Punakha to a field beside the river where a modern helicopter is resting in wait. In a pioneering partnership with the Royal Bhutan Helicopter Service, the kingdom’s fledgling air ambulance fleet, well-heeled travellers staying at COMO’s properties can now be among the first to visit some of the kingdom’s most remote corners. The Scenic Heli-Adventure includes two flights — from Paro to Punakha via the rarely-visited Laya Valley, and from Punakha to Paro via the Utsho Tsho, the Turquoise Lakes of the Labatama Valley, though I’ve managed to hitch a ride in the opposite direction, visiting Laya en route to Paro’s international airport.

With a roar from the turbines that reverberates off the mountain sides, British captain Nik Suddards pilots the new Airbus helicopter up Punakha Valley, offering a bird’s eye view of the Nalanda Monastery and the sacred peaks of Jigme Dorji National Park, home to snow and clouded leopards, Himalayan black bear, red pandas, and ancient glaciers. After 40 minutes in the air we circle the tiny village of Laya at 3800 metres above sea level, the kingdom’s highest settlement.

Located in one of the most remote and least developed parts of the country, Laya is home to the semi-nomadic Layap people, a relatively affluent community that harvests cordyceps, a rare fungus used in Chinese and Tibetan traditional medicine. Their Bey-yul, or the hidden paradise, is protected from mischievous spirits by an ancient gate at the village entrance, visible as the helicopter descends. Foreigners are extremely rare in Laya, as are helicopters, and after landing above the village, we’re greeted by curious locals, among them two young sisters. I’m the first foreigner they’ve ever meet, which puts smiles on all our faces.

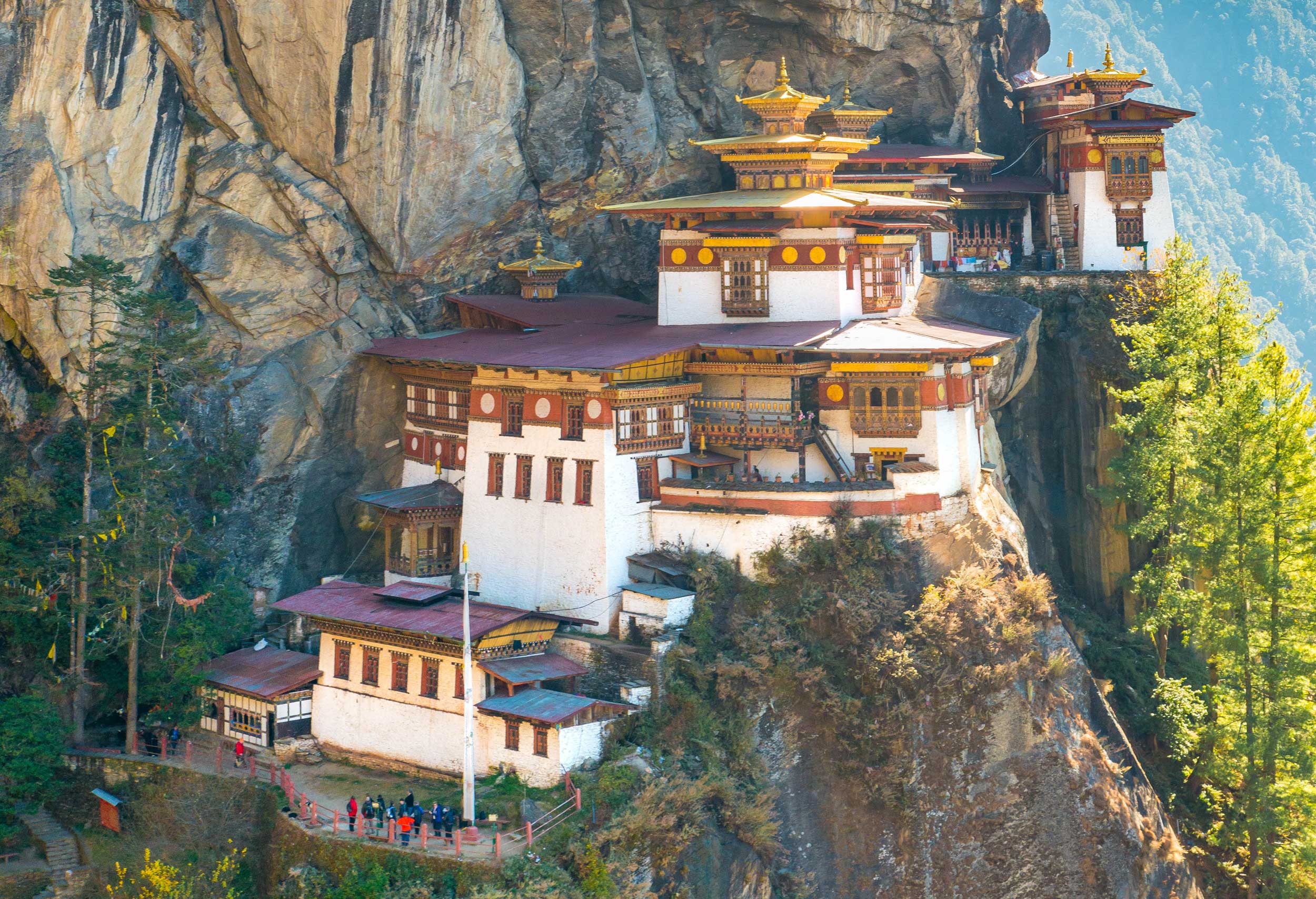

From Laya the helicopter itinerary heads south to the rice terraces, mountain fortresses, and ancient shrines of Paro. We skirt frozen alpine pools, the jagged tips of lower peaks seemingly within reach as we descend into the valley, passing Paro Taktsang, the iconic Tiger’s Nest monastery, on approach to the runway.

Our final day is spent climbing to Tiger’s Nest, a feat in itself. A prominent Himalayan Buddhist site, the Taktsang Palphug Monastery was built in 1692 on the side of a dramatic cliffside, and while visitors no longer have to risk life and limb on tiny footholds set into the rock, the hike up the opposite cliff, and then the 700 stairs down into the canyon and back up again to the monastery (which need to be repeated on the hike home) can be a little challenging. But that’s the beauty; once you make it to the shrine and drink in the soaring views across the kingdom’s mountainous interior, you’re guaranteed your biggest Bhutanese smile yet.