The History of Pilgrimage

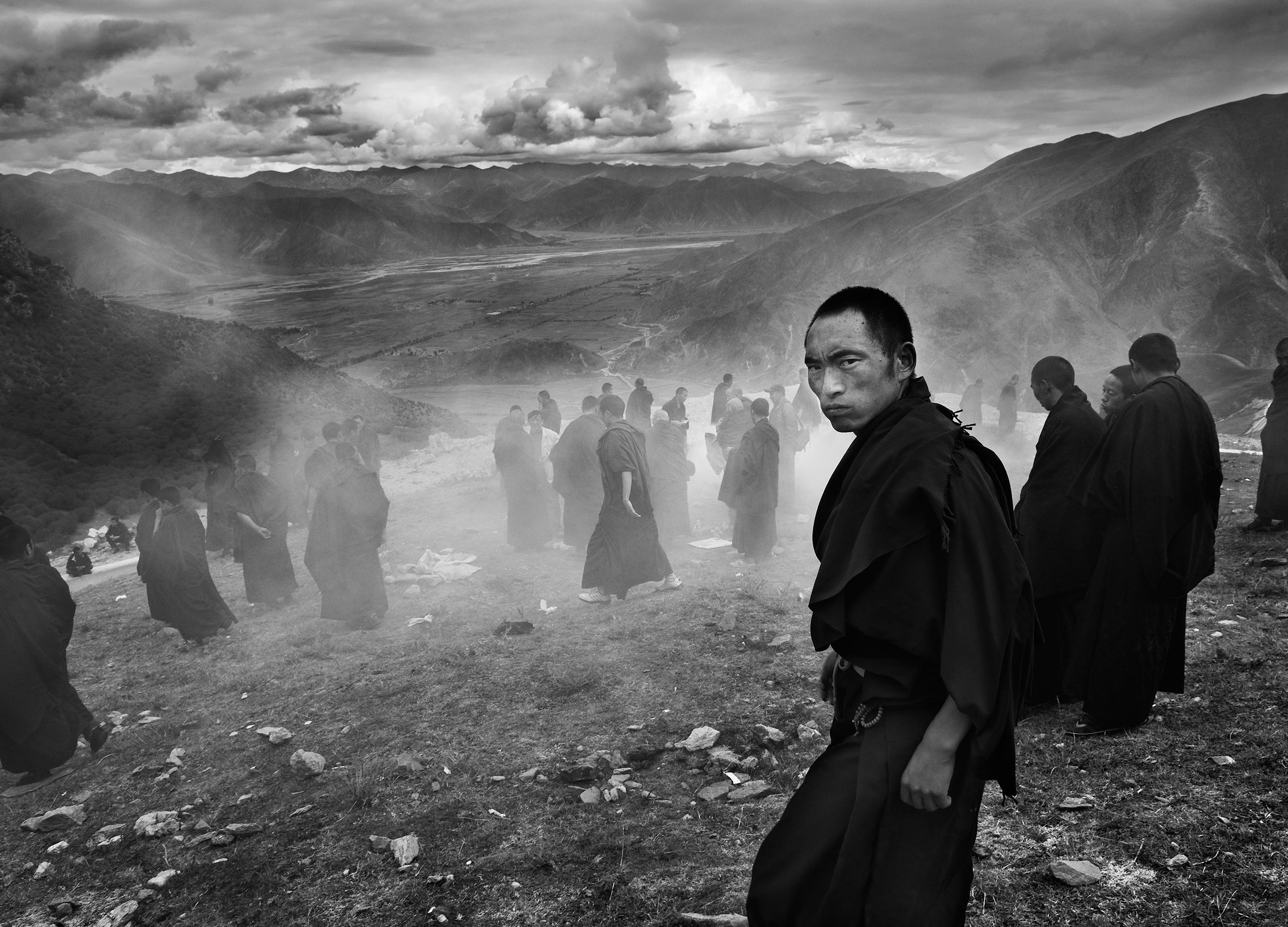

Pilgrimages are an age-old tradition stretching back through the history of nearly every major religion. Muslims journey to Mecca and Jews to Jerusalem. Buddhists travel to Tibet, and Hindus to Benares. For many pilgrims, it was a journey made for religious or civil penance. For others, it has been the opportunity to get close to divinity. Reaching the sacred destination is said to invoke healing, spiritual awakening or lead the visitor to their innermost desires.

In India, it is believed by Hindus that bathing in the Ganges River can heal not just physical ailments, but also absolve the sins of the bather — from this life and those before. The upper reaches of the river, where it runs swiftly, is considered especially purifying. The bather has to grasp an anchored chain in order to avoid being carried away by the current. Despite being ranked as one of the most polluted rivers in the world, each year millions of people bathe in it, and bottle the water to give to the sick, the dying and those getting married.

In Japan, pilgrims have been enjoying the spectacular views from the Kumano Kodo, or Ancient Trail, since the 10th century. The path winds its way to sacred shrines, and tea houses and hot springs wait for tired travellers at the end of the day. In Tibet, it is said that the Mount Kailash pilgrimage can erase the sins of a lifetime. The 52-kilometre walk around the mountain has been popular with Tibetans for 15,000 years and many complete the 15-hour walk in one day. Others crawl the entire distance and take about four weeks to complete it. Buddhist teachings say that if a pilgrim can make it around 108 times, they will reach Nirvana.

Pilgrimages have also been an important tool for social movements. In 1930, Mahatma Gandhi protested against the British salt tax by walking 400 kilometres across India to the sea at Dandi. At the end of the 24-day march, his 78 original followers had turned into thousands. By the time Gandhi bent down and scooped up a handful of salt from the sea bed, he had spoken to thousands of people across the country, spreading his ideas about standing up for India’s independence. The Salt March is remembered as one of the most significant organised challenges to British authority.

Similarly, in the United States, Martin Luther King’s iconic “I Have a Dream” speech was the culmination of the March on Washington in 1963. Over 250,000 people travelled from across the nation for the rally, one of the largest in the country’s history. On the morning of the march, over 100 buses an hour were streaming through the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel towards Washington. It was the mass volume of these pilgrimages — where people joined together for a common purpose — that caught the world’s attention. In both cases, the memories of these famous pilgrimages now inform the attraction of these sites for today’s visitors, allowing their ideologies to live on.

However, contemporary pilgrimages aren’t reserved only for the religious or politically-inclined: a broad range of destinations have meaning and are revered across the globe. For Elvis aficionados, Graceland is a must-see, while Abbey Road draws countless Beatles fans each year. Those who want to walk in the footsteps of famous movie stars head to the Hollywood Walk of Fame, while those who worship soccer stars head to Maracana Stadium in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Some of these examples may seem superficial, yet for many they represent a highly emotional, inspirational, and evocative journey; a celebration of places, individuals, meanings and identity.

Increasingly, we are seeing a new type of pilgrimage — one that is independent, creative, and personal. One modern pilgrim, Anna McNuff, believes the reason people go on a journey like this is because they are looking for something, “only they’re not sure what they are going to find.” As the daughter of two Olympians, Anna always had the goal of representing Britain in rowing at the Olympics, but the intense training was a strain, both physically and emotionally. At the age of 23, after years of training and dutiful commitment, Anna realised that she had other dreams. Rather than looking for external recognition, she says, “I just want to be proud of myself. I want to look in the mirror and say, ‘I’m proud of you’.” Anna sensed there were other ways of achieving this, but she was unsure as to exactly what hers would be. “We are all in search of our purpose,” she notes. “That’s why I started this journey.”

Anna completed a 17,700 kilometre cycle trip through every state of the U.S. in 2013. “I love it because when I’m running, most of the time I’m not thinking about running,” she said. “You get into a state where you completely transcend the situation. You get space and clarity… it gives me a chance to step back and pick and choose what parts of my life I like, what parts I want to work on.” Couple that with the excitement of travel, foreign cultures and meeting new people, and there is potential for an unforgettable experience. Through this process, Anna has discovered that she loves getting young people excited about sports and adventures. She was offered so many opportunities as a child, she says, and now it’s her chance to pass that passion along to kids who may not be able to afford what her family could.

Another contemporary pilgrim, Phil Brotherton, has constructed a journey to honour his great-grandparents’ generation, those who fought in the First World War. In commemoration of the 100th centenary of Gallipoli, the 38-year-old undertook a 5600-kilometre solo expedition from Asiatic Turkey to England. The pilgrimage saw him walking, cycling and mountaineering from Istanbul over three sets of mountains, including the Dolomites. Along the way, he laid down 2015 poppies as an original tribute to those who lost their lives. Further, as an accident 11 years ago left Phil with a head injury from which he developed epilepsy, this pilgrimage was a way to push his own physical boundaries as well as to honour the fallen.

For Leo Murray, a year-long pilgrimage was a major stepping stone to discovering what he wanted to do with his life. The 28-year-old has always enjoyed a good time at festivals, parties and raves. He spent nearly six years working as a DJ, but eventually came to realise that his role was helping people to ‘escape’ their everyday lives through drugs and alcohol — and not in a good way. “A lot of people in the world are looking to achieve happiness. I wasn’t really sold on the contentment equation we are told to believe in,” he said.

Leo came to realise that he wanted to combine his love of music and parties, but not at the cost of the other people and the world around him. He and his wife spent a year travelling to their destination — the Burning Man Festival in Nevada, United States. Their path took them to the top of the Himalayas, temples in India, Peru and Cambodia, and a permaculture design course within a Mexican eco-resort. In taking a spiritual path and learning about permaculture on the way, for Leo the trip wasn’t just about reaching the party — it was a journey to a sustainable lifestyle. These days, Leo has managed to combine both: he devotes his energies to festivals which incorporate workshops that inspire positive change, and runs his own business, Why Waste, which reduces the amount of rubbish put in landfills. He credits his pilgrimage for the inspiration to change his life.

As for Anna McNuff, finishing her pilgrimage is something for her to be proud of. “People used to find themselves through religion,” she said. “This has a similar theme.” Choosing the right final destination for a pilgrimage is important, but, most agree, the greatest fulfilment comes from the journey itself. And while it may feel like a penance when the backpack straps are cutting into our shoulders and even our blisters have blisters, this is when the moments of clarity arrive.