Our first recorded superfoods are muffins and wine. There is a scrap of an article in a Jamaican newspaper, published on 24 June 1915, which pronounces: “He had changed the tenor of his mood, and wisely written wine as superfood.” Thirty-four years later, in 1949, a Canadian newspaper reported on a Mr LeBourdais, who was busy extolling “the muffin’s worth as superfood that contained all known vitamins and some that had not been discovered.”

Now, muffins and wine are the antithesis of what we think superfoods are these days. Large pillowy balls of sugar and fat that come in different flavours and configurations? Innumerable types of grapes squeezed and bottled in specific ways producing hazy hangovers and bad decisions? These are modern indulgences, often eaten and drunk to excess, responsible for obesity, ill health, and addiction.

The superfoods of today are for the virtuous, the ethical and the health-conscious. They are lauded for their unparalleled nutritional value. They are ancient grains or leafy greens or round, red fruit. Their names conjure up the exotic or the wild unknown; quinoa, chia, kale, acai, moringa. They provide perky, wholesome alternatives for jaded taste buds.

Trending on coconut water

Atoifi Hospital in the Solomon Islands is a green two-storey building, anchored by a field with a fenced-off satellite dish in the corner. In 1999, doctors admit a stroke patient. The man is dizzy and weak, choking on liquids and vomiting. He is put on an intravenous drip. Unfortunately, the hospital is running out of IV fluids to sustain him. Their next supply is two days away and there is no money to fly in more. Meanwhile, the man is rapidly dehydrating.

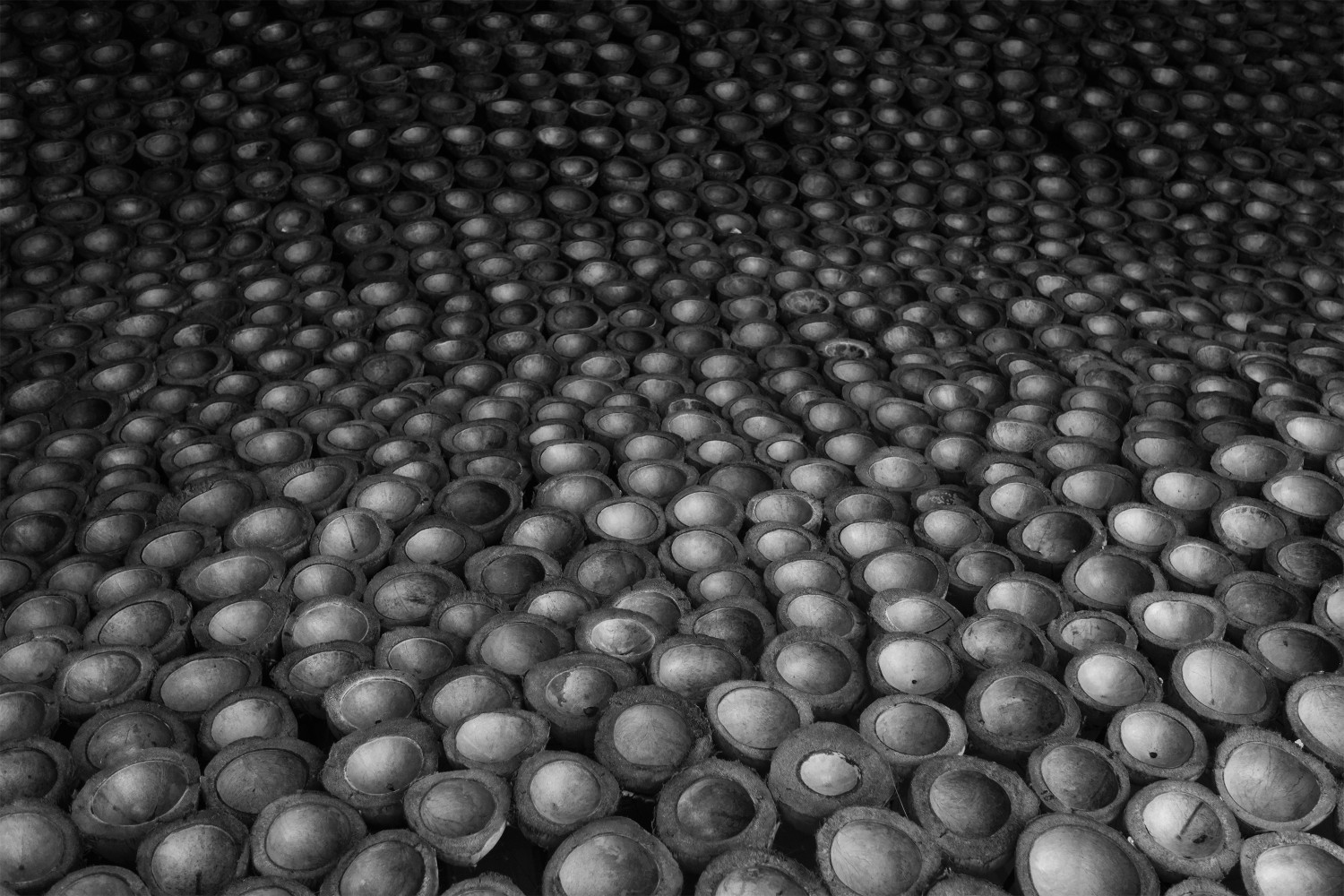

A snap decision is made. Doctors inject coconut water into the man’s IV drip. Coconut water contains a cocktail of electrolytes (potassium, chloride, calcium) that supports hydration. It is the next best thing to IV fluids and on the islands, there are always coconuts. There are pictures of the set-up. A needle is jabbed into a coconut and it hangs from the IV stand like a strange modern art installation. The man is kept alive on a coconut water IV drip for two days and is discharged 39 days later.

Fast forward to a freezing December in New York and I am standing bewildered in an aisle of a Whole Foods on Union Square. I am inexplicably craving coconut water. Normal water will not do. Luckily, it is 2014 and in Manhattan, coconut water is totally a thing. I do not need to be in a tropical climate to find it. North American sales of coconut water went from zero in 2004 to nearly US$400 million in 2013. I am elbowed aside by New York University students in skin-tight jeans and plaid shawl coats, hair artfully unbrushed or twisted in carefully constructed knots. The girls buy coconut water, I suspect, because they want a cure for their hangovers and, like the doctor at Atoifi Hospital, they have heard all about its magic powers of hydration. The NYU students make buying coconut water look nonchalant and cool, and I want in.

I check each person’s coconut water of choice. I need all the help I can get. According to Dr Marion Nestle’s book What to Eat, there are around 320,000 food and beverage products in the United States, with the average supermarket stocking 30,000 to 40,000 of them. Standing out from competitors is, largely, all about marketing. The coconut water selection in Whole Foods stretches for half an aisle. The shelves are awash with bottles: big and small, squat and slender, curvy and boxy. The colour palette is all surprisingly similar in greens, blues, whites and greys. There are the trendy bottles, minimal and clean, heavy on the sans serif fonts. Then, there are the ones like Vita Coco, labels splashed with tropical palm trees and bright blue skies, really leaning hard on coconut water’s roots. In 2011, the company featured Rihanna in its ad campaign for its ‘tropical’ flavoured iteration. The pop star is freshly blonde and grinning in a crop top and shorts emblazoned with a perky pineapple print.

A year later, Vita Coco pays a US$10 million settlement to consumers complaining about the overblown health claims (“15 times the electrolytes found in sports drinks”) made by the company. A number of nutritionists attest that if we really need to hydrate quickly, glasses of water and some bananas will do the trick, or alternatively, a less expensive sports drink. Today, Vita Coco remains undaunted, with US sales of around $240 million in 2013, close to a 60 per cent share of the market. Madonna, Matthew McConaughey and Demi Moore are all investors in the company. Meanwhile, Fair Trade USA reports that farmers from places like Indonesia and the Philippines receive $0.11-0.20 cents per coconut. On average, they will receive about a dollar a day throughout the year. I come out of Whole Foods with the Harmless Harvest “100% Raw Coconut Water”. I pay US$4.99 for a 470 millilitre bottle.

Honestly? Coconut water is delicious. The last time I drank it was seven years ago. My friend and I hired a taxi to take us from Phnom Penh, Cambodia to Siem Reap. Our driver flew us through a classic Southeast Asian landscape of palm trees and rice fields. At a gas station, we stretched our legs and across the street, behind a stack of coconuts at a roadside stall, a man beckoned at me with a grin. In his outstretched hands, he cupped a green baby coconut, the top hacked off. The nostalgia was overwhelming. I thought of my childhood in the Philippines, tipping a coconut into my mouth, the juice running down my forearms and into my mouth, brown husks littered at my feet. I crossed the road and with two straws, my friend and I drink from one coconut. The liquid is warm, earthy, and sweet. There is nothing like it.

To the market for quinoa

In the early nineties, NASA scientists were on a mission to find plants that could be grown in space stations. The objective was to establish a ‘controlled ecological life support system’ that could solve the myriad challenges associated with supporting life on long-term space missions. In 1993, quinoa was compared with grains like barley, corn, rice and wheat and declared the fairest of them all. It was a strong contender for space because of its optimal balance of fat, protein, carbohydrates, and amino acids and the relative ease with which crops could be grown.

Ten years later, the demand for quinoa has increased 18 times over and the cost to buy it in a market in La Paz, Bolivia — the world’s biggest supplier of quinoa — has increased by about 10 times more, from US$0.16 per kilo to US$1.15. On one hand, the appetite for quinoa presents Bolivian farmers with a golden opportunity to earn money, a tough thing to do in one of the poorest Latin American countries, where 82 per cent of rural populations live below the poverty line. However, if demand continues to grow, so will the pressure to dedicate more land to growing quinoa, at the expense of crop diversity and food security.

This presents its own risk. There is no denying that Western appetites can be fickle. The need for large swathes of quinoa crops could be wiped out with a simple turning of the food trend tides. Restaurants are already sourcing the rarer black or red quinoa, customer appetites seemingly sated with the original. A recent slew of articles on the internet ask, “What’s the Next Quinoa?” in the same way gossip magazines and blogs speculate about the next ‘It girl’. There are a couple of rival ‘It’ grains; one from Mexico called amaranth, and the other, teff, from Ethiopia.

I decide that quinoa should meet my mother. She is 61 years old, well-travelled, and loves avant-garde fashion. Surprisingly, she has never eaten quinoa. She struggles to pronounce the name for a start, butchering the odd procession of consonants and vowels. I tell her about the South American farmers, struggling to keep up with demand from developed countries. I let her know about the local populations in Bolivia and Peru who once subsisted on this high-protein superfood but are now theoretically priced out of the market. Her eyes glaze over; I am fast losing her attention. So, I go for something a little jauntier, “Did you know that astronauts grow quinoa in space stations?” My mother perks up, “Where can I try it?” she says.

I know exactly the place. It is a trendy new restaurant, Loretta — all gleaming light, wooden floors, leather booths, exposed concrete floors, and stacked watermelons on enormous dishes arranged just so. Without checking, there it is — a black quinoa salad with pulled chicken, amaranth, cucumber and flat leaf parsley for US$12. In one fell swoop, I am able to deliver two of the hottest ‘It’ grains to my mother, in Wellington, New Zealand, approximately 10,000 kilometres from where these grains are grown.

I wait until my mother finishes and ask what she thinks. She shakes her head, wipes her lips on a napkin. Her verdict? “You shouldn’t eat this if you have to go to a meeting. I need a toothpick. Maybe those South Americans don’t mind talking with specks in their teeth.” Her response surprises a laugh out of me. It is good to know that there are some who refuse to be seduced by trends and instead focus on the pragmatic.

Everything is super

Eat muffins and drink wine all day and chances are, we will be rolling to an early grave. Quinoa for lunch and coconut water after a gym session will keep a body strong and healthy, working to support us at a more efficient (though not necessarily cheaper) rate. We are what we eat. It used to be that simple.

Now, eating quinoa and drinking coconut water is more than just the act of putting nutrients into our body to keep us going. As a consumer, we have the power not just to consume, but as food writer, Michael Pollan put it, to be a co-creator. Our preferences drive and shape market trends and forces. They can make us part of the enrichment of the lives of a South American farmer or a tiny cog in a country’s agricultural downfall. They determine what a pop star will endorse and whether a celebrity gets to cash in on the stocks they have invested. We are buying into superfoods, standing in front of aisles and aisles of choices and consequences.