Amazon Task: Ecuador’s Waorani Fight for the Rainforest

From the beginning of my journey into the depths of the Amazon rainforest, I knew I was on a truly different kind of adventure. On day one my translator and guide Luis Garcia leaned towards me and warned, “Our canoe won’t be stopping for a while, because we’re now travelling through the Red Zone.”

The Red Zone — I learned — is a region of the Amazon where ‘uncontacted’ tribes are feuding with the indigenous Waorani (also known as Huaorani) with whom we were heading down the Shiripuno River. “So, watch out for people who might throw spears from the nearby riverbank,” Luis cautioned. Death in this part of the Amazon happens suddenly and frequently.

I’ve always preferred intrepid travel — no schedule, no pre-arranged itinerary. So, I figured, what could be better than a two-day journey downriver through a place called the Intangible Zone?

The Intangible Zone is a large section of Ecuador’s Yasuni National Park inhabited by at least two of the planet’s last uncontacted tribes. Ecuador officials report two, but my hosts, the Bameno Waorani, insist there’s one more family group in the region still living a Stone Age way of life that the government doesn’t even know exists.

The Waorani are classified as a ‘recently contacted’ tribe, having been approached sporadically over the last few decades by missionaries and workers from the burgeoning oil industry. Bameno warriors speak openly about having speared the first outsiders to come into contact with the tribe

Oil drilling is the reason for my visit. The Natural Resources Defense Council, an American environmental organization has sent me to Yasuni, to find remote tribes still living their traditional hunter-gatherer life, and report on how they are being affected by oil drilling that is closing in on them.

Yasuni is regarded as the most abundant and diverse ecosystem on the planet. But underneath Yasuni there is oil. Recently a well was drilled about 25 kilometres from Bameno and more are planned. Now the Bameno’s leader, Penti Baihua, is on a crusade to save the rainforest and his tribe’s way of life from steadily encroaching oil drilling.

As we slowly slipped downriver, Waorani pointed and shouted excitedly at caiman on the riverbank. Tapirs, capybaras, anacondas and toucans ran, waddled, slithered and flew overhead, and the river teemed with turtles and piranhas. The Waorani still hunt for almost all their food, so seeing these animals signalled (the signalling was to them, not me) that their environment was healthy and their future secure.

Although, that last point is debatable. Penti’s quest to preserve the rainforest has forced him out of the jungle to work with various government, tribal and nonprofit leaders. So, as a way of raising funds, he’s allowing small groups of tourists from nearby Coca to visit his village and stay for a few days.

A visit to Bameno is an anthropological trip back in time. And, talking with Penti feels much like sitting down for an evening conversation with Native American tribal chiefs Geronimo and Sitting Bull. My translator Luis and I lived in Bameno for a week alongside the Waorani. Two seasoned adventurers from the United States named Dave and Bob joined us.

The four of us immersed ourselves in the Waorani way of life — sleeping in an open-air bamboo hut, spear-hunting wild boar and shooting poisoned darts from bamboo blowguns at howler monkeys swinging through the forest canopy. When not hunting we enjoyed the freedom to explore Bameno and the surrounding jungle on our own.

Firing a poisoned-dart from a blowgun is an unparalleled experience. I still can’t figure out the physics — how a puff of breath can force a tiny dart from the end of a 12-foot-long bamboo tube at the speed of a bullet. The evening before our hunt, we watched Waorani hunters brew jungle vines to produce curare, the neurotoxin that instantly paralyses whatever animal is struck by a dart dipped in the poison.

Traditionally, adult Waorani eschew clothes for body paint, but I noticed many villagers wearing T-shirts and shorts. Luis explained that the adults in the village were following our lead, and feeling a little uncomfortable about it.

That afternoon I emerged from our hut free of shirt, pants and boots. Dressed only in a bathing suit (okay, it’s a process) I roamed the village until I met up with Luis, on his way to visit an old Waorani friend.

Inside Mipo’s home, three naked women painted their bodies from head to toe with beautiful tribal designs. The women motioned for me to join them, and I spread my arms wide. The one-room hut filled with giggles as the women struggled to apply their paint through the hair on my arms. Shaking her head, one of the women named Welpa called me a monkey. I responded with a monkey impression that started everyone in the hut howling with laughter.

One morning Penti and a tribal elder named Kempery guided us deep into the rainforest to see a blaze of vibrantly-coloured parrots, toucans and macaws swooping down like a mini-tornado to feed at a natural clay lick. Along the way, we paused to admire a kapok tree as large and as old as a California redwood. And, we learned how to find and eat ants from a jungle lemon ant tree: Spot the little critters as they march up and down the trunk, lift off a raised section of bark, and scoop up the ants with your tongue.

On our last night, my companions and I joined Waorani men and women in a cultural exchange of traditional song and dance; our not-quite-rousing rendition of Take Me Out To The Ballgame left the villagers speechless. Later we drifted off to sleep (or tried to), to a resounding chorus of jungle noises.

Penti funds his trips to Quito, Ecuador’s capital with the proceeds he receives from the few tourist groups he allows into his village each year. He hopes this small-scale tourism won’t dilute the Waorani’s hunter-gatherer way of life, but western influence is creeping in. Younger villagers are covering their bodies by wearing shorts and T-shirts, and the customary diet is changing. Traditionally Waorani feast when wild boar is plentiful, and fast for days when game is scarce. But these days when Penti makes his trips to Coca and Quito, he returns with rice, which has become a diet staple.

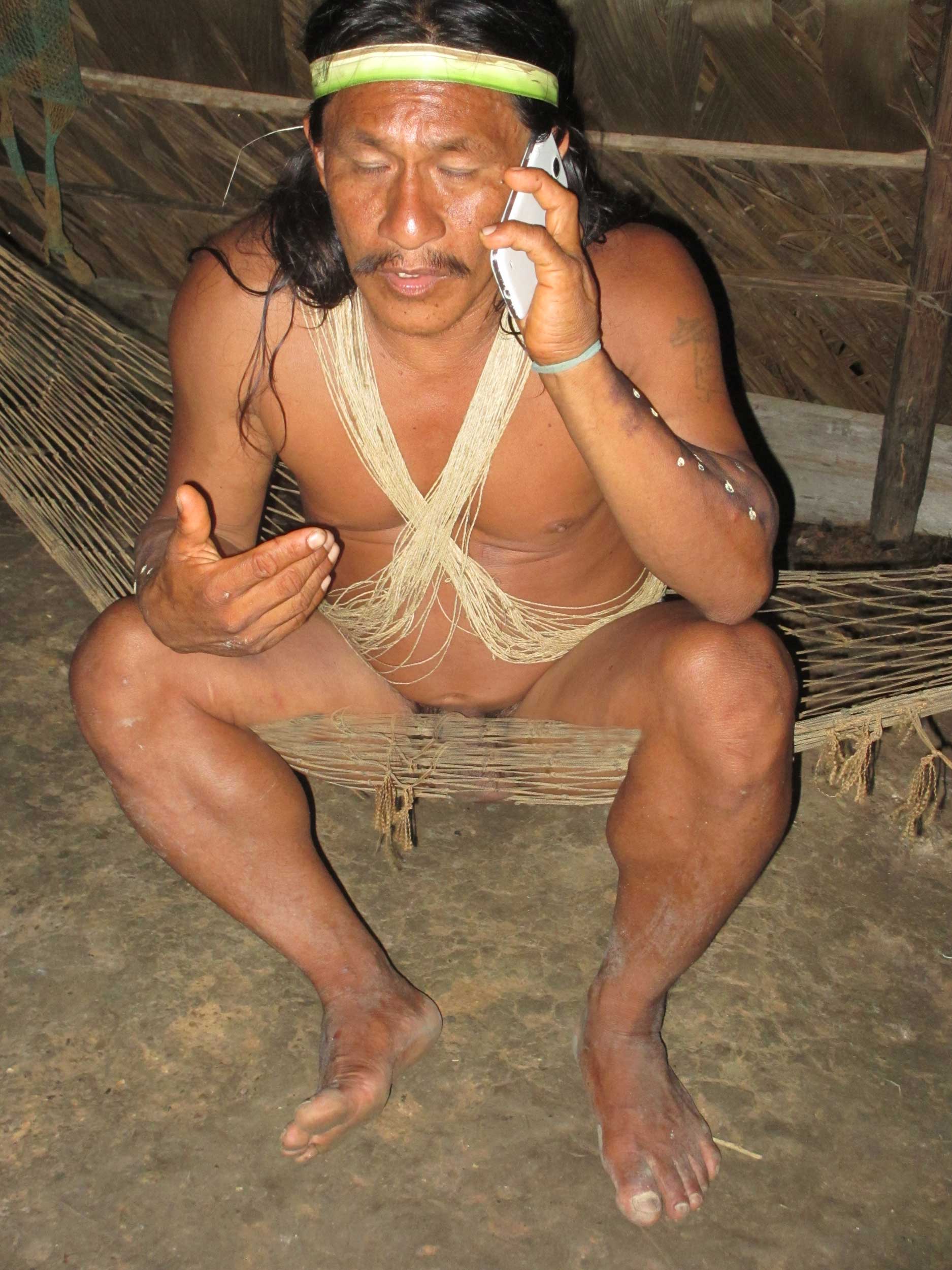

Recently, Penti made his most significant concession to the modern world — a diesel generator with a satellite dish. Each evening for an hour or two the village receives a wireless connection that allows Penti to stay in contact with various officials and his pro bono attorney in New York. An unintended ‘benefit’ of the generator is the discovery of social networking by the village’s younger generation.

Penti realises he’s taking a risk by opening up his village to the outside world. But he knows he must do whatever is necessary to prevent the spread of oil drilling in the region. A few more oil wells will mean more oil spills, colonisers and potential death for his people and their way of life.

The Red Zone feud between Waorani and the uncontacted tribes has taken the lives of more than 20 tribespeople in recent years. According to Penti it’s a direct result of the oil industry’s incursion. Oil wells on the edge of the Intangible Zone have shrunk the rainforest for all traditional tribes. That pressure, Penti says, is the primary reason different rainforest Waorani kill each other. Penti is sure that if the rainforest continues to shrink something approaching warfare will break out.

So Penti, reluctantly, makes his trips to Coca and Quito and he leaves Bameno visitors with a message to spread.

“Tell people that deep in the rainforest there are Waorani in Bameno who are happy to live the way they live. Maybe one or two will listen.”

ESSENTIAL INFORMATION

- Several small airlines offer daily flights from Quito to Coca.

- For those on a budget, there’s a daily bus service. It’s a ten-hour trip and costs around US$10.00.

- The canoe trip from Coca to Bameno takes two days each way. So visitors should allow at least a week for a visit to Bameno, which means three days living in the village. Be prepared to sleep on the ground during the journey to and from Bameno.

- Accommodation in Bameno is primitive, but visitors are given a bed with overhead mosquito netting.

- Food is simple and somewhat dependent on the success of Bameno hunters —wild boar, wild turkey and rice are staples.

- There are no showers, or baths in the village, but there’s a piranha-filled river nearby. Bameno children play in the river all the time.

- A guide/translator is not essential, but for those who want to learn about the Waorani as well as experience their culture, Coca biologist Luis Garcia can be contacted at [email protected].

- A stay in Bameno can be arranged through Huaoranicommunitytours.com.