Unmasked

Masks can disguise and deceive, charm and captivate, entertain and entice. What makes masks so enigmatic? Is it the element of disguise and intrigue, or a connotation of other-worldliness? Perhaps it is their alignment with ritual and deep tradition. In any case, there is no doubt that with their ability to enable coquetry along with a sense of anonymity, masks facilitate the chance to escape, to take on another persona.

As a mask artisan, I have been running workshops and creating masks for clients around the world for more than a decade. It is an arena full of joy and creativity, dealing with such pressing dilemmas as which mask to choose, or which colours to wear to a much anticipated party. Character, glamour, ethnic, wall-art, and theatrical masks — creating them is all in a wonderful day’s work for me.

I was first drawn to masks on a visit to Venice in the 1980s. Not only did I fall in love with the best city in the world in which to get lost, the beautiful mask shops around every corner captivated me and triggered my passion for all things masquerade. This love grew exponentially during subsequent visits to Venice, when I observed and absorbed various techniques and styles that I carried back to my home studio to adapt in my own way.

Disguise & Deceit

Masks have been worn in cultures throughout the world for thousands of years, but perhaps never with such fervent pageantry as in Venice. Masquerade balls were particularly popular amongst the hedonistic upper classes during the 15th century Renaissance period.

Flamboyant and fabulously extravagant occasions, the balls allowed masked guests to dress so as to be unidentifiable, and part of the game was to work out one another’s identities. Wearing a mask meant people could behave in ways they might not otherwise. One’s identity could be changed dramatically: emotions concealed, character transformed. Gamblers wore masks so no one could read their facial expressions. Criminals would wear them so they could not be identified. Noblemen who had lost their money and fallen from grace could beg on the streets behind a mask and no one would know who they were. On the other hand, servants wearing a mask could be mistaken for a nobleman. The practice of disguise and deceit was alive and well in Venice.

Concealment & Revelation

One Venetian mask that acts as a veil with a difference is the rather odd Moretta mask. ‘Moretta’, meaning ‘small and dark’, describes this mask most aptly. It is small, round and black, with circular eyeholes and no mouth. It is worn only by women, often with a veil as a shroud. The Moretta kept the beauty of feminine features hidden.

It also kept women quiet, as the mask was held in place by a button clenched between the front teeth. Its plain design was meant to conceal emotions. However, despite its rather unflattering appearance, this concealment was seen as a means of enticement. The mask could be removed quickly by releasing the button to reveal the woman beneath. However, as things gradually got rather out of hand, an anti-masquerade movement emerged within Venice. Laws were introduced banning the wearing of masks, with heavy penalties inflicted on those who broke the law. Today, however, this heritage is celebrated at

the Venice Carnivale, a well-known and illustrious event with a special history, lavish costumes and a rich sense of mystery. Being part of it one day is on my bucket list.

A decorative mask can be a glamorous dressup; a little frivolous, or even daring. Hiding behind a mask in this way allows the wearer the sense of escapism the early Venetians enjoyed. It is a way of being who we might want to be, or who we know we are not. As a means of disguise, rendering anonymous the person beneath, this may bring a sense of comfort for the wearer, though it may equally be unsettling for the observer.

Theatre & Entertainment

Used on stage, masks can portray moods and characters and bring an element of fun and intrigue. One of the earliest uses of masks for drama was in ancient Greece, in the 6th century B.C. Masks from that period generally incorporated over-exaggerated facial features and enclosed the entire head. These characteristics created a resonance chamber for the voice of the actor, allowing audiences in the huge amphitheatres to hear them more clearly. The ancient art of Japanese Noh theatre, which is still alive today, is considered a highly refined means of artistic expression using masks, movement and lighting to convey subtleties of emotion and character.

Many types of masks are also used in traditional Italian Commedia dell’Arte. Whilst this is a highly structured art form, with characters and situations precisely defined, there is also plenty of scope for actors to embellish their parts in the moment. It is all about constant surprise. Cut to more modern times, and masks used in movie-making continue to bring characters to life, with such examples as Darth Vader and the iconic mask from Scream both instantly

recognisable and emblematic of a meta-narrative on the nature of masks themselves.

Protection & Provision

From primitive to modern times, wearing a safety mask has served to protect the wearer from physical or spiritual harm. Medieval armour incorporated a protective helmet with facial covering and strategically placed slits to see through, while gas masks used in wartime saved many lives. Practical masks are used regularly today with safety in mind: think surgeons, firefighters, sportspeople, and tradespeople. Given that the face alone facilitates the senses of sight, smell, taste and hearing, it does indeed warrant protection. However, masks are also used to guard against misfortune from supernatural spirits that the wearer or their community might fear. Masks that are believed to have such protective qualities are often in the figure of a god or mythical being, sometimes with a grotesque appearance so as to frighten away evil spirits. An elaborate and fearsome mask coupled with aggressive gestures and threatening sounds is indeed frightening and mesmerising.

Healing & Connection

Masks are often linked to the great milestones of life such as coming of age, seasons, and illness or death. These are all times of transformation, and wearing masks for such events is ingrained in many cultures. In African tribes, initiation ceremonies are common as boys reach adulthood, while for women, masks may be worn as part of fertility rituals. Ceremonies designed to give thanks for the land and to ensure the abundance of future harvest can incorporate the wearing of masks.

Some people believe that by wearing a specific mask they might connect themselves with ancestral or other unearthly spirits. There is a belief that putting on such a mask can provide a link between the living and the dead, the natural and supernatural. Having the power to heal as well as harm, masks have been sought after to cure illness, and wearing a mask is often accompanied by the beat of a medicine drum, chanting or music. In Iroquois society, masks decorated with horsehair, to represent a spirit with the power to cure disease were used for healing.

Burial masks played an important role in ancient times. Placing a mask over a dead person’s face as a preserver of personality was common in many communities. As a mark of respect and honour, especially for someone of important social standing in society, the mask would preserve and protect during transition to the afterworld where its power would transform them into a god or protective spirit. Such funerary masks were prized. Without doubt, there is a highly spiritual connection when masks are used in these ways.

The Romans also collected and displayed the death masks of their ancestors as an important part of the affirmation and embellishment of their lineage. This was especially important for the patrician tribes of the Capitoline and Palatine Hills elevated above the surrounding mass of the ‘plebs’.

Decoration & Collection

While some masks are intentionally destroyed after they have been used in specific ceremonies, others are built to last but are damaged and disintegrate over time, requiring preservation or restoration by mask artisans.

Those masks that last can be collected as a travel memento, as a cultural artefact for studying or simply for aesthetics. They are often passed down through generations, just as mask-making techniques are.

Old and new masks are a popular decorative item in homes, with designs drawing on traditional and modern styles. Such masks often do not have openings for the eyes and/or mouth, their form and function being somewhat different to those that are worn.

Incognito

As travellers, we journey to far-off lands and, in effect, we encompass all that mask-wearing entails: as we discover new corners of the world, we do so largely anonymously. The unfamiliarity of masks can frighten and startle, but they also generate connection. Similarly, going out of our comfort zone to gain new experiences amongst strangers, we absorb their customs and practices, often participating and always learning. New bonds are formed. As we travel, pleasure and purpose are wrapped together and the stories come tumbling out. Mask-wearing, personified.

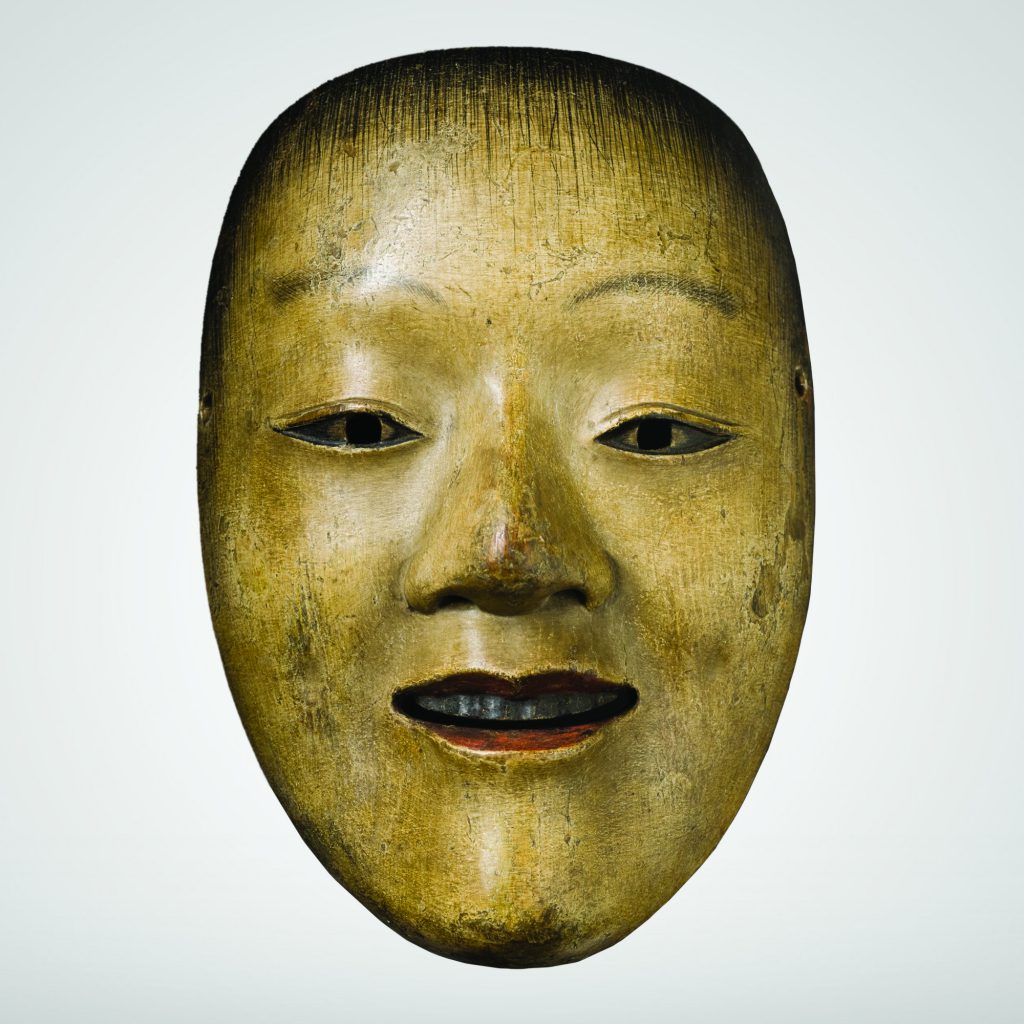

Noh Mask — Japan

Carved from Japanese cypress, painted with natural pigments and dating back to the 14th century feudal period, these highly stylised masks enable skilled performers to convey the mood and character of a range of roles in Japanese Noh theatre. With each slight tilt of the head or subtle lighting adjustment, a new expression is communicated.

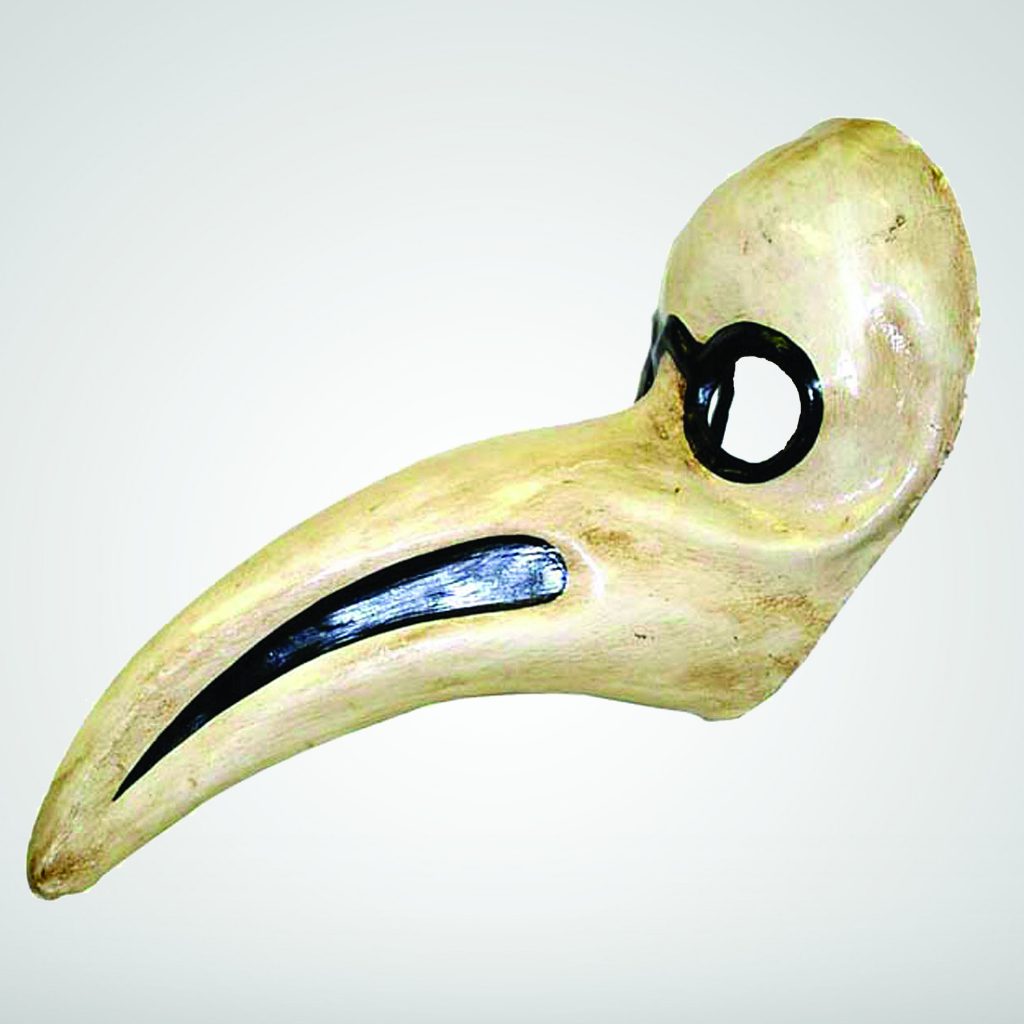

Dottore della Peste Mask — Europe

In demand in medieval Europe, plague doctors were fully covered to ward away spirits and smells, believed to be the cause of illness. Their attire included a distinctive beak mask with glass-covered eyeholes, and two small nostril slits stuffed with herbs and spices to help purify the air.

Yup’ik Mask — Alaska

Created by Yup’ik Eskimos, these masks play a central role in dancing ceremonies and storytelling gatherings during long Alaskan winters. Each carved mask tells its own unique story, honouring life in the Arctic environment. The muted colour palette complements intricate, diverse and expressive designs reflecting nature, animals and humanity.

Gurulu Raksha Mask — Sri Lanka

One of several raksha (demon) masks used in Sri Lankan festivals, rituals and cultural dances, the Gurulu portrays a mythical bird devouring a snake and is believed to bring good luck and protection. Made of wood and painted in vibrant colours, raksha masks are apotropaic — used to ward off evil influences.